Chopping the top of a car, a modification that dramatically lowers the roofline, stands as one of the most visually striking and transformative customizations in automotive history. Often considered the ultimate expression of custom car artistry, the chopped top fundamentally alters a vehicle’s profile, lending it a sleeker, more aggressive stance. This article delves into the fascinating history of chopped car roofs, tracing its origins from the early days of automotive customization, primarily focusing on metal-topped coupes and sedans from the 1930s onwards. While the modification of convertible and roadster tops predates coupe and sedan chops due to simpler pillar structures, this exploration centers on the more complex and groundbreaking technique of lowering metal roofs. Let’s embark on a journey to uncover the influences and early pioneers of this iconic custom car styling element.

Early Influences on Top Chopping

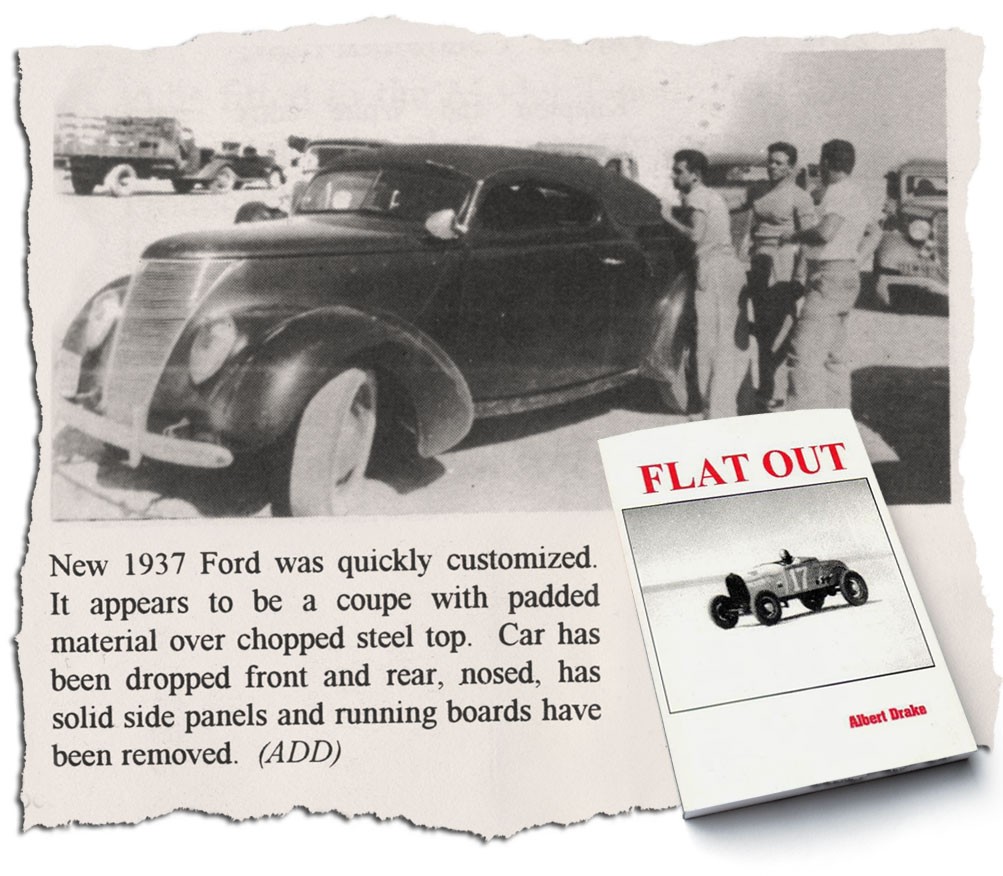

Pinpointing the absolute originator of the chopped top remains an elusive task. Custom car culture, as we recognize it, began to flourish with the emergence of 1933 and later model cars. It took a few years for bodywork artisans to begin experimenting with significant roofline alterations. To date, one of the earliest documented examples of a chopped metal top is a 1937 Ford sedan. This innovative modification involved lowering and reshaping the roof to create a hybrid silhouette, blending sedan and coupe aesthetics. Interestingly, the roof’s metal structure was then covered in canvas, mimicking the appearance of a padded top, yet it was fundamentally a solid, lowered metal roof. Precise dating of this pioneering customization remains challenging, but evidence suggests it was executed within a year or two of the car leaving the factory. Regrettably, in those nascent years of custom car culture, modifications were often not extensively photographed or documented. These early works were not always perceived as significant events worthy of detailed records. Despite this lack of formal documentation, piecing together the history of top chopping is an intriguing endeavor, and hopefully, this exploration will encourage readers to share their knowledge and fill in the historical gaps.

An early example of a chopped top, this 1937 Ford sedan features a lowered and vinyl-wrapped roof, likely modified in 1937 or 1938. The alteration showcases the nascent stages of top chopping techniques.

Design Sketches and Coachbuilding Heritage

Several factors likely converged to inspire early customizers to embark on top chopping. Automotive design sketches from the 1930s, created by both independent designers and those within major car manufacturers, played a crucial role. These conceptual drawings, intended to explore future model directions, frequently depicted cars with lowered stances, extended wheelbases, and reduced window heights, culminating in low-profile roofs. This design approach conveyed an image of speed, power, and enhanced aesthetic appeal. While these initial designs often underwent revisions to accommodate practical considerations like passenger headroom (allowing gentlemen to wear hats, a common request), the allure of the original, lower-roofed sketches persisted. Car advertisements and brochures often subtly incorporated these design elements, presenting vehicles with more streamlined, lower rooflines to enhance their desirability.

Art Ross, renowned for his design sketches for Duesenberg and other luxury marques in the mid-1930s, consistently featured coupes and sedans with minimized side windows and raked windshields. These design choices inherently suggested what we now recognize as a “chopped” look. Numerous other designers of the era explored similar low-roofline aesthetics in their sketches, contributing to a growing visual vocabulary that would influence custom car builders.

Coachbuilt cars, typically based on high-end chassis from manufacturers like Duesenberg, Packard, and Cadillac, offered another avenue for low-roofline inspiration. These bespoke vehicles, commissioned by affluent clientele, prioritized aesthetics and exclusivity over mass-market practicality. Designers working with coachbuilders had greater creative freedom to craft streamlined, low-slung rooflines that surpassed the production limitations of major automakers. Tasked with satisfying a single, discerning client, coachbuilders in the early to mid-1930s began pioneering designs with smaller windows, raked windshields, and elegantly tapered rear roof sections.

While these coachbuilt creations were fundamentally new bodies rather than modified production cars, they embodied the visual essence of what would later be termed “chopped.” Their streamlined, low-roofed profiles undoubtedly captured the imaginations of young car enthusiasts in the mid to late 1930s. California, with its burgeoning car culture fueled by favorable weather and expanding road networks, became a hub for coachbuilding and early customization. While the mild climate might have seemingly favored convertibles and roadsters, the economic realities of the time likely steered some enthusiasts towards more affordable coupes and sedans as starting points for their custom projects.

Originally a 1932 Duesenberg four-door sedan, Bohman & Schwartz re-bodied it in 1937 with a striking, low-roofline design. This coachbuilt example, featuring aerodynamic principles and leather-like Zapon cloth panels, exemplifies the influence of streamlined aesthetics.

LeBaron’s 1937 coachwork on a Lincoln Model K chassis showcases a design reminiscent of an enlarged, chopped 1935-36 Ford 3-window coupe, demonstrating the cross-pollination of design ideas.

The Impact of Sales Illustrations

Car advertisements and sales brochures of the mid-to-late 1930s, and even extending into the 1940s, predominantly utilized illustrations rather than photographs. This preference stemmed from the artistic license illustrations afforded. Artists could subtly manipulate car proportions, depicting them as longer, lower, and generally more appealing than their photographic counterparts. In the pre-digital age, crafting a “better-than-real-life” illustration was a common marketing strategy. Many of these illustrations showcased cars with significantly lower rooflines than the actual production models. This deliberate lowering enhanced the car’s perceived length and sleekness, making it more visually enticing in promotional materials. This pervasive visual cue of lower rooflines in car advertising undoubtedly influenced young, aspiring custom car builders in the late 1930s and early 1940s, inspiring them to experiment with roof modifications.

Advertisements for the 1935 Ford coupe and 1936 Ford sedan illustrate the practice of depicting cars with lower rooflines than production models. This artistic manipulation aimed to enhance visual appeal and influenced early customizers.

Padded Convertible Tops as Precursors

The Carson Top Shop pioneered the “French top” padded top design in 1935. By around 1937, they were producing chopped padded tops. While a detailed discussion of chopped padded tops is reserved for a future article, it’s important to acknowledge their role. Modifying convertible tops, particularly the windshield pillars and soft top frames, was inherently less complex than altering the all-metal roofs of coupes and sedans. The aesthetic of these lowered, padded-top customs may have served as a visual catalyst, prompting innovators to explore the more challenging realm of chopping metal tops.

Dry Lake Racing and Streamlined Forms

The dry lake racing scene in California during the early 1930s provided another influential backdrop. Young enthusiasts flocked to the vast, flat lakebeds to race their Model A Fords. To minimize air resistance and maximize speed, some racers lowered their windshields. In some cases, convertible tops were also modified to match the lowered windshields, creating a streamlined, low-profile appearance. These modifications, born from the pursuit of speed, resulted in a tougher, more elongated, and powerful visual aesthetic. This functional streamlining for racing likely resonated with early customizers, perhaps initially inspiring top chopping for performance gains on the dry lakes, before evolving into a purely stylistic modification for street customs.

Ed Hagthrop’s chopped 1935 Ford Coupe at one of the mid 1940’s dry lake events.

Early Publications and the “Chopped Top” Terminology

The earliest documented mentions of top chopping techniques in custom car publications date back to 1944. Dan Post, through his typed “Mimeographs” series titled Remodeler’s Manual for Restyling your car, disseminated informal notes and observations on body alterations aimed at achieving lasting automotive style. The first of these manuals appeared in 1944. Notably, the term “Chopped Top” was not yet in common usage in these early publications. Instead, the technique was referred to as Lowering Hard Tops, distinguishing it from the simpler process of lowering convertible tops. The term Chopping Tops emerged around 1949, marking a shift in terminology. Edgar Almquist also contributed to the dissemination of custom styling knowledge with his series of Custom Styling Manuals, the first of which, published in 1946, included a detailed description of the roof lowering technique. While the exact origin of the term “Chopping Tops” remains debated, photographic evidence from the Barris Compton Avenue shop, dating back to approximately 1946, suggests its usage was becoming established around this time.

Dan Post’s 1945 “Remodeler’s Manual for Restyling your Car” provides early documentation of top lowering techniques, though not yet using the term “chopping.” These manuals served as crucial resources for early customizers.

Edgar Almquist’s 1946 Custom Styling Manual also described the “Lowering Metal Tops” technique, further contributing to the formalization of custom car modifications in print.

This 1947 Dan Post “Master Custom-Restyling Manual” provides a written description of the top cutting process, demonstrating the growing interest in and documentation of this technique.

An image from the 1947 Dan Post manual illustrating chopped tops, showcasing a 1934 Ford Vicky and a partially visible Mercury coupe, highlighting early examples of the modification.

Dan Post’s 1949 “Blue Book of Custom Restyling” marks a significant point, using the term “CHOPPED” in an illustration guiding readers on how to cut a coupe top. This publication helped solidify the terminology.

George Barris, in a 1950 Motor Trend magazine interview, shared his insights on custom restyling, including top chopping. This mainstream media attention further legitimized and popularized the technique within the broader automotive world.

A 1950 Motor Trend article featuring George Barris showcased a 1940 Ford coupe undergoing a heavy top chop, visually demonstrating the process to a wider audience.

Research into early chopped tops reveals a trend towards less radical modifications in the initial years, compared to the more dramatic chops of the late 1940s and early to mid-1950s. This likely reflects a developing understanding of balanced aesthetics. Early customizers prioritized proportionality, matching the degree of top chop to the car’s overall stance. As lowering suspensions became more common in the later 1940s, facilitated by improved road conditions, deeper top chops became necessary to maintain visual harmony. Of course, exceptions always exist, but generally, early chops were more restrained.

Another characteristic of early chopped cars is the frequent retention of drip rails. While sometimes shortened, particularly on cars with filled rear quarter windows, drip rails were rarely fully removed and smoothed in the manner that became prevalent in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Early chops also often exhibit a somewhat boxier, less streamlined aesthetic compared to the sleeker, more flowing lines that emerged later in the decade.

The 1936 Fords: Early Chopping Pioneers

Evidence suggests that 1936 Ford models, both 5-window coupes and two-door sedans, were among the earliest recipients of chopped metal tops. Intriguingly, the now-popular 3-window coupe variant appears to have been less common in these initial chopping experiments.

Santa Monica ’36 Ford 5-Window Coupe

One of the earliest datable chopped customs is a beautifully restyled 1936 Ford 5-window coupe, likely customized in the late 1930s. Photographs of this car show it bearing 1940 California license plates. Dean Bachelor, who photographed the car, attributed the restyling to Santa Monica Body Works. While details about this shop are scarce, it was likely a general body shop commissioned by the Ford’s owner to perform custom bodywork, a common practice in the early custom scene. The car features a subtly chopped top, perfectly balanced with its stance—a testament to early customizers’ refined sense of proportion.

Restyled by Santa Monica Body Works, this 1936 Ford 5-window coupe showcases an early, subtly chopped top, along with other modifications like removed running boards and a narrowed grille, exemplifying early custom car aesthetics.

This 1936 Ford sedan, photographed from Mark Murray’s grandfather’s collection, is believed to be one of the first chopped ’36 Ford sedans, demonstrating the early adoption of the technique on sedan models.

Mark Murray’s 1936 Ford Coupe Chop Photos

Rare photographs shared by Mark Murray depict a 1936 Ford coupe undergoing a top chop, likely around 1948. These images offer a glimpse into the actual process of early top chopping, a subject not frequently documented in photographs from that era.

Tommy Jamieson ’36 Ford 5-Window Coupe

Howard Fall restyled this 1936 Ford 5-window coupe for Tommy Jamieson in 1939-1940. This custom was considerably more radical than many contemporary examples. It featured channeling over the frame, raised 1937 Ford front fenders, a modified 1938 Ford hood, a chopped top with vertical pillars, a custom grille, and solid hood sides. The rear fenders remained stock but incorporated 1938 Ford teardrop taillights, and 1940 Mercury bumpers replaced the originals. Howard Fall finished the car in a two-tone green paint scheme.

Tommy Jamieson’s heavily restyled 1936 Ford 5-window coupe, customized in 1941, showcases a more radical approach to early chopping with a distinct upright rear roofline.

Bob Fairman / Jimmy Summers ’36 Ford Coupe

Bob Fairman’s 1936 Ford 3-window coupe, featuring full fadeaway fenders, is another early example of a chopped coupe. It appears to have been built around 1941, potentially concurrently with George Barris’s ’36 Ford 3-window. While the exact craftsman who performed the chop is uncertain, it may have been Jimmy Summers, or perhaps Bob Fairman himself while working at Summers’ shop. The chop on Bob’s coupe is relatively mild, especially compared to later, more extreme examples.

Bob Fairman’s 1936 Ford 3-window coupe, customized while working for Jimmy Summers, exhibits a mild top chop and filled rear quarter windows, reflecting early 1940s styling trends.

George Barris ’36 Ford Coupe

George Barris’s personal 1936 Ford Coupe, customized in 1941, represents his first foray into full custom car building. It embodies a Nor-Cal aesthetic often associated with Harry Westergard—long, sleek lines, a high hood, and a “speedboat” stance. While Westergard’s direct involvement is unconfirmed, Barris’s mild top chop on this ’36 Ford demonstrates a keen sense of balanced proportions.

Jack Calori Ford

The Jack Calori Coupe, a chopped ’36 Ford coupe restyled by Herb Reneau in 1948, stands as one of the most influential chopped ’36 Fords ever created. Built in Long Beach, California, it embodies the Harry Westergard style, though direct influence is uncertain. Its impact was amplified by its cover feature in the November 1949 issue of Hot Rod magazine, a highly popular publication at the time. Herb Reneau’s chop on the Calori Coupe is believed to be his first metal top chop. The magazine feature likely inspired countless enthusiasts across the US to undertake similar modifications on their own ’36 Fords.

The Jack Calori 1936 Ford coupe, featured in Hot Rod magazine in 1949, became a landmark example of chopped top styling, inspiring a generation of customizers.

Bob Pierson ’36 Ford Coupe

Bob Pierson’s 1936 Ford Coupe is another iconic example. Initially restyled as a mild street custom in 1947, its top was chopped in 1949 to allow it to compete in a different racing category at the dry lakes. The top chop, executed by Bob and Dick Pierson and Harry Jones, was not solely functional; it was meticulously crafted for aesthetic appeal as well. This chopped coupe became a familiar sight in the Southern California custom car scene of the late 1940s and early 1950s.

Bob Pierson’s 1936 Ford coupe, initially restyled in 1947, showcases its pre-chop form with DeSoto bumpers and Appleton spotlights, representing a milder custom style.

By 1949, Bob Pierson’s 1936 Ford coupe featured a striking chopped top, transforming its appearance and purpose, transitioning from street custom to dry lake racer.

A less refined chop on a 1936 Ford 5-window coupe from Michigan, likely dating back to the early to mid-1940s, illustrates the varying levels of craftsmanship in early top chopping attempts.

Beyond the ’36 Ford: Expanding the Chopped Horizon

While 1936 Fords were early favorites for top chopping, they were not the only models to receive this treatment. FoMoCo (Ford Motor Company) vehicles dominated the custom scene in the early years, but chopped tops soon appeared on various makes and models. 1939 and 1940 Mercury coupes became particularly popular candidates from the mid-1940s onwards. Their factory roofline, almost appearing hardtopped and somewhat ungainly, made them prime for a dramatic roof reduction.

Many early chopped cars retained their drip rails, sometimes shortening them, especially when combined with filled rear quarter windows—a styling cue possibly borrowed from chopped padded convertibles. Filled rear quarter windows were indeed another popular custom modification in the early years, contributing to a sleeker, more coupe-like profile, even on sedans.

Dick Fowler’s 1938 Ford Coupe, chopped at Barris Shop around 1946, demonstrates a more substantial top reduction and the early adoption of shaved drip rails for a smoother appearance.

Earl Bruce 1940 Ford Coupe

Earl Bruce’s 1940 Ford DeLuxe business coupe, purchased new in 1939, was immediately taken to Jimmy Summers’ shop for a full chop and filled quarter windows. While some accounts credit Roy Hagy with the chop for a previous owner, Tommy Winship, the car was undoubtedly chopped very early, likely in late 1939. Early film footage from October 1940 already shows the car with its fresh chop.

Earl Bruce’s 1940 Ford coupe, filmed at an SCTA event in October 1940, showcases a very early chopped top, highlighting the rapid adoption of this modification.

A later side view of Earl Bruce’s 1940 Ford coupe reveals the significantly altered roofline, stretched in the center, with filled rear quarter windows and rounded door corners, illustrating evolving chop techniques.

Bob Creasman’s 1940 Ford coupe, chopped in 1943 by Bob Creasman and the Brand Brothers Body Shop, mirrored the styling of Earl Bruce’s coupe. Four inches were removed from the top, which was then extended to ensure proper alignment of pillars. Filled rear quarter windows were also incorporated.

John Williams ’40 Ford Coupe

Olive Hill Garage, run by Art Lellis and Jerry Moffatt, created refined customs in the early years, including John Williams’ 1940 Ford coupe. Chopped in late 1939 or early 1940, it featured a peaked hood, Lincoln bumpers, and a beautifully proportioned chop, retaining its rear quarter windows, unlike some contemporaries.

An unidentified 1940 Ford chopped coupe, likely from the early 1940s, showcases a well-proportioned chop and minimal other modifications, resembling a stylized illustration from the period.

Don Lee ’40 LaSalle

Don Lee, known for restyling cars for clients, created a 1940 LaSalle coupe with a unique approach. Instead of significantly lowering the roof, the windshield was leaned back while maintaining its original height, creating a lower roof profile. The rear quarter windows were filled, and the entire top was smoothed. A similar treatment was applied to a 1941 Cadillac for Clark Gable and Carole Lombard.

Don Lee’s 1940 LaSalle coupe demonstrates an alternative approach to roof lowering, using a leaned-back windshield to achieve a lower profile, alongside filled rear quarter windows.

Chopped Sedans Emerge

While coupes and convertibles were naturally favored for customization, chopped sedans also emerged as compelling custom creations. Whether driven by owner preference or budget constraints, sedans offered ample interior space and, when chopped effectively, could achieve stunning aesthetics.

Chopping sedans often presented greater challenges, particularly with forward-slanted rear body sections. Reshaping the rear of the body to harmonize with the new roofline was frequently necessary. However, successful sedan chops yielded impressive results.

Barris Kustoms’ 1938 Ford Sedan

Barris Customs masterfully restyled a 1938 Ford Standard sedan with a heavy, flowing chop, smooth hood sides, and a Packard Clipper grille. The rear body section was extensively reshaped to integrate seamlessly with the lowered roof. This work, executed in 1946-47, exemplifies Barris’s early expertise in complex top chops.

A 1939 Ford 2-door sedan, heavily chopped in the mid-1940s, showcases an early sedan chop style, possibly with a “boxed” roof extension, illustrating the adaptation of chopping techniques to sedan bodies.

Eldon Gibson 1940 Oldsmobile

Eldon Gibson’s 1940 Oldsmobile 4-door sedan, damaged in a fire, underwent a unique restoration and customization. Modern Motors, a Cadillac/Oldsmobile dealer, repaired the fire damage and simultaneously chopped the top. In a distinctive approach for a sedan, the B-pillars were aligned during the chop, and the stock windshield was leaned back, while the rear window was leaned forward. The A- and B-pillars were reshaped to create a cohesive design. This radical 4-door sedan chop, executed in 1941, was exceptionally rare for its time and remains so today.

Eldon Gibson’s 1940 Oldsmobile 4-door sedan, radically chopped in 1941, represents an exceptionally early and unusual example of chopping a four-door sedan, showcasing innovative techniques.

1939-40 Mercury’s and Barris Mastery

The Barris shop played a pivotal role in refining top chopping techniques. Early attempts, while sometimes successful, occasionally resulted in awkward proportions. However, Barris-chopped tops consistently achieved excellent aesthetics. Sam and George Barris’s continuous experimentation and learning are evident in the evolution of their chop styles.

Sam Barris is credited with chopping one of the first 1939 Mercurys, Jim Kirstead’s, around 1946. Early “in-progress” photos of this car reveal a somewhat rough initial stage, indicating Barris’s shop was still developing its approach to the Mercury coupe’s complex roof shape. Pre-shaped panels were not yet readily available in the early days, so body men often utilized spare body parts, skillfully reshaping them to fit the modified C-pillars.

Jim Kirstead’s 1939 Mercury coupe, one of the first Mercury chops by Barris, reveals the early, more labor-intensive process of shaping the C-pillars, highlighting the evolving techniques.

Bill Spurgeon’s 1939 Mercury, restyled by Barris in 1946, showcases a less extreme chop than Kirstead’s, with a more factory-like roofline and subtly modified windshield, demonstrating Barris’s developing style.

Comparing ’40 Mercury Chops: Zaro vs. Matranga

Comparing Johnny Zaro’s 1940 Mercury, built around 1948, with Nick Matranga’s late 1940s/early 1950s chopped 1940 Mercury highlights the evolution of chopping styles. Both based on the same model, they exhibit distinct approaches, built just a few years apart.

An in-progress photo of Johnny Zaro’s 1940 Mercury, circa 1948, reveals a more conservative chop style, emphasizing the car’s original lines with a lower roofline.

The Johnny Zaro Mercury features a more conservative chop, closely adhering to the original car’s lines but with a lowered roof and subtle streamlining, achieved by molding the rear roof section to the body. This approach yielded a more aggressive stance while maintaining a recognizable Mercury profile. To achieve proportional side windows, a significant amount was removed from the top, resulting in a smaller windshield.

Barris learned from these earlier chops. For Nick Matranga’s 1940 Mercury, Sam Barris employed a different technique. He reduced the windshield height less than the overall top chop, effectively raising the windshield slightly into the roofline. This brought the windshield height into better proportion with the side windows. By the time Nick’s Mercury was restyled in the late 1940s/early 1950s, streamlining was a dominant stylistic trend. Sam aimed for a smoother, more flowing roofline on Nick’s car compared to previous Mercury chops. Utilizing pre-shaped metal panels from California Metal Shaping, he crafted curves that seamlessly integrated the top into the body’s “catwalk.” This new roof shape created the illusion of a single, monolithic body, contrasting with the original design where the roof appeared as a separate component with chrome trim. The low roof and flowing lines of Nick Matranga’s Mercury gave it a distinctly modern look. Barris further enhanced the design by replacing the straight side window posts with elegantly curved, handmade, chrome-plated channels. Nick Matranga’s Mercury is widely considered the definitive chop for the 1940 Mercury, though contemporary high-end builders continue to refine and evolve this iconic style.

A comparison of Johnny Zaro’s conservative 1940 Mercury chop (top) and Nick Matranga’s streamlined, ultimate chop (bottom), both executed by Sam Barris, illustrates the evolution of chopping styles and techniques over a short period.

This concludes the first part of our exploration into the history of chopped car roofs. The story is far from complete, and future articles will delve into cars from 1941 onwards, further tracing the evolution of this transformative custom car modification. We encourage readers to share any additional information or early photographic evidence of pre-1940 chopped top customs. Stay tuned for part two…