Introduction

The importance of early detection and intervention for mental health disorders is increasingly recognized in healthcare. Identifying and treating these conditions early can significantly improve patients’ quality of life, reduce healthcare costs, and prevent complications arising from co-existing mental and physical health issues.[1, 2] Numerous organizations, including the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), advocate for routine behavioral health screening in primary care settings.[3, 4] The USPSTF specifically recommends screening adults for depression, alcohol misuse, and drug abuse, emphasizing the necessity of readily available diagnostic follow-up and behavioral health services. Despite these recommendations, the implementation of systematic screening for common mental health conditions like depression in primary care practices remains suboptimal.[5] This gap may be attributed to various factors, including financial constraints in behavioral health, and insufficient infrastructure for referrals and diagnostic support.

The shift towards value-based payment models in healthcare encourages a more integrated and holistic approach to patient care.[6] Policy changes and payment reforms, such as the Medicare Shared Savings Program, are now incentivizing behavioral health screening in primary care. For instance, participation in shared savings programs often requires behavioral health screening, prompting healthcare organizations to enhance their infrastructure in this area. These trends, coupled with the emphasis on early intervention, integrated care models (like Accountable Care Organizations and patient-centered medical homes), payment parity, and the adoption of electronic health records, are driving the need for effective Primary Care Screening Tools For Mental Health. While informal screening methods are sometimes used,[1] structured and validated instruments are more effective in accurately identifying behavioral health disorders.[3, 4, 8]

Primary care settings require screening tools that are not only valid and reliable but also brief, easy to administer, freely available, and accessible.[9] Determining the specific mental health conditions to screen for should be guided by the needs of the patient population served by each practice.[10] Additional factors influencing tool selection include time constraints in clinical settings,[10, 11] workflow considerations, and whether a tool is self-administered or requires clinician administration. Crucially, the psychometric properties of screening tools, particularly their validity and reliability, must be carefully evaluated. It’s also vital to remember that screening is only the first step; improved patient outcomes depend on comprehensive education, training, and clinical pathways that facilitate timely and effective treatment, [12] along with accessible resources for diagnostic follow-up, as highlighted by the USPSTF.[3, 10, 12]

Bundled screening, which involves assessing for multiple behavioral health disorders simultaneously, offers an efficient approach. This can be achieved by using either a single multiple-disorder tool or administering several brief, single-disorder tools concurrently. This systematic review aims to identify and evaluate publicly available, psychometrically sound, and brief screening tools—both single-disorder and multiple-disorder instruments—suitable for screening adults for common behavioral health conditions encountered in primary care. These tools are intended for primary care physicians (PCPs) who are looking to proactively screen their patient populations based on diagnostic risk factors and who have, or are developing, the necessary behavioral health infrastructure for follow-up, as recommended by the USPSTF. This review aims to provide PCPs with the information needed to select the most appropriate primary care screening tools for mental health for their practice needs, considering factors like applicability in primary care and suitability across diverse populations.

Methods

Search Strategy

This systematic literature review adhered to the Institute of Medicine (IOM) guidelines.[13] Relevant studies on behavioral health screening tools were identified through comprehensive searches of PubMed, PsycINFO, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Health and Psychosocial Instruments (HaPI) databases. Search terms included “primary care” combined with various terms related to screening and mental health conditions, such as “screening,” “screening tools,” “instruments,” “assessment,” “alcohol,” “behavioral health disorder,” “behavioral medicine,” “anxiety,” “depression,” “emotional health,” “mental health,” “mental illness,” “mental disorders,” “substance use,” “substance abuse,” “substance-related use disorders,” and “suicide.” The search was limited to English language articles published between 2000 and 2015, with the final search conducted on May 4, 2017.

Article Selection

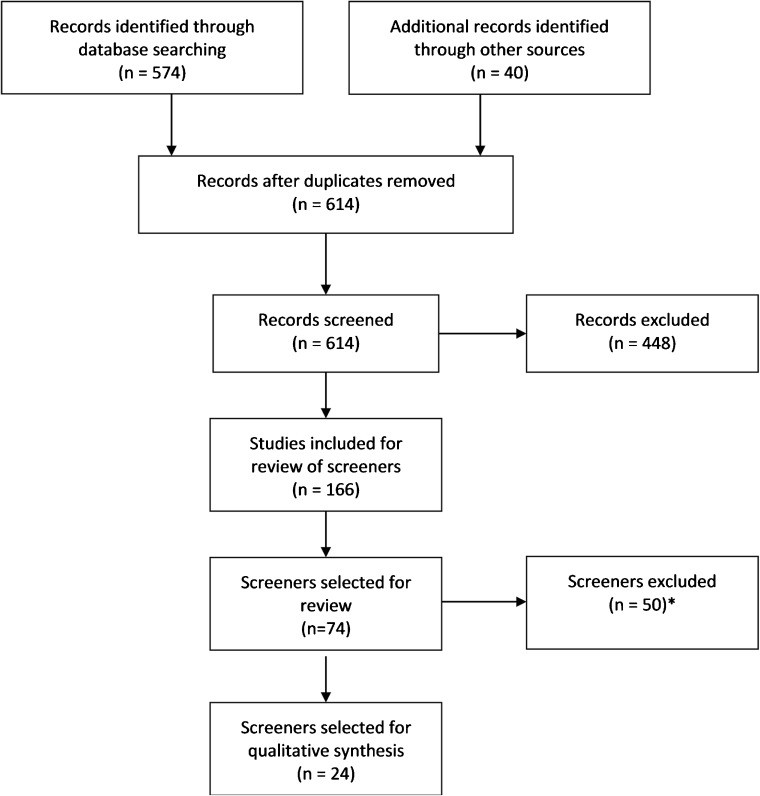

Abstracts were selected based on their evaluation of publicly available, non-proprietary tools designed to screen for anxiety, depression, and substance use disorders. Inclusion criteria required that the screening tool (1) had undergone psychometric validation, (2) was intended for adults aged 18 and over, and (3) had been studied in English in North America or Western Europe. Exclusion criteria included articles focusing on general behavioral health screening processes, studies of Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) programs, and tools that: (1) were global functioning or quality-of-life scales without specific behavioral health condition focus; (2) were initially developed for research rather than clinical practice; (3) assessed only cognitive impairments like dementia or Alzheimer’s; (4) screened for conditions less commonly managed exclusively in primary care, such as eating disorders and severe mental illnesses like bipolar disorder or schizophrenia; or (5) were specifically designed for older adults in settings outside general primary care clinics (e.g., inpatient, nursing homes). Additional relevant articles were identified from reference lists (see Figure 1). Screening tools were categorized as either (1) multiple-disorder tools (including subscales of larger assessments or tools assessing multiple conditions in one instrument) or (2) brief, single-disorder tools (assessing only one condition with five or fewer items).

Figure 1. Article Selection Flow Chart

Flow chart detailing the systematic article selection process for primary care mental health screening tool review.

Data Abstraction

The primary criterion for evaluating the utility of primary care screening tools for mental health in this review was their psychometric properties. Data was collected on each tool’s characteristics relevant to primary care settings, including the targeted behavioral health condition(s), sensitivity, specificity, and established cut-off points for positive screens. Information was also gathered on the population studied and the gold standard measure used for psychometric validation. For tools initially developed for primary care, psychometric data from the original validation study was used. For tools developed in other settings, data was taken from the first study that evaluated them in a primary care context identified in the literature review.

The assessment of psychometrics focused on criterion validity, specifically the tool’s accuracy in identifying the presence or absence of a disorder. Three criteria were used to evaluate validation strength: (1) use of a robust gold standard (e.g., clinical interview), (2) testing of sensitivity and specificity in primary care settings, and (3) achieving sensitivity and specificity rates above 75% (considered indicative of good to excellent performance). Sensitivity refers to the proportion of true positives (correctly identified cases), while specificity refers to the proportion of true negatives (correctly identified non-cases). These metrics can vary based on the chosen cut-off point, the population, the setting, and assessor experience.[14] The optimal cut-off point is the threshold that maximizes both sensitivity and specificity, effectively identifying those with the disorder while correctly excluding those without it.

To assess each tool’s practical utility in primary care, data was collected on administration time and whether it was self-administered or provider-administered. If administration time was not reported, the number of items was used as a proxy: (1) 1–4 items indicated ultra-short tools (under 2 minutes), (2) 5–14 items indicated short tools (2–5 minutes), and (3) 15 or more items indicated standard tools (5+ minutes).[15]

Results

The review identified 24 primary care screening tools for mental health, comprising 13 short instruments (five or fewer items) and 11 longer instruments. Notably, eight of these tools were subscales or adapted versions of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) and Patient Stress Questionnaire (PSQ).

PHQ and PSQ-Derived Tools

Table 1 details eight screening tools derived from the PHQ and PSQ, which have been refined for individual administration and scoring. These subscales were developed and tested as a unit, ensuring no item overlap. Primary care practices can selectively combine these tools to create tailored screening protocols without compromising psychometric properties due to content redundancy, although context effects based on administration order should be considered.

Table 1. Screening Tools Derived From PHQ and PSQ for Multiple Mental and Substance Use Disorders

| Scale | Target Conditions | Population and Gold Standard | Psychometrics | Application in Primary Care Practices |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP | SE (%) | |||

| Patient Health Questionnaire, 15 items (PHQ-15)[16, 17] | Somatization syndromes, somatoform symptoms, somatoform disorders | Primary care setting in the Netherlands; measured against SCID | ≥6 | 78 |

| Patient Health Questionnaire, 9 items (PHQ-9)[19–21] | Major depressive disorder | Primary care patients; measured against clinical interview | ≥10 | 88 |

| General Anxiety Disorder scale, 7 items (GAD-7)[27] | General anxiety disorder | Primary care clinics; measured against clinical interview | ≥10 | 89 |

| Panic disorder | ≥10 | 74 | ||

| Social anxiety disorder | ≥10 | 72 | ||

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | ≥10 | 66 | ||

| Patient Health Questionnaire, 4 items (PHQ-4)[30] | Depression and anxiety; consists of the first 2 items of the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 | ≥6 (≥3 for both) | ||

| Patient Health Questionnaire, 2 items (PHQ-2)[16, 21, 32] | Depression | Primary care and obstetrics-gynecology clinics; measured against clinical interview | ≥3 | 83 |

| General Anxiety Disorder scale, 2 items (GAD-2)[33] | GAD | Primary Care Clinic; measured against clinical interview | ≥3 | 86 |

| Panic disorder | ≥3 | 76 | ||

| Social anxiety disorder | ≥3 | 70 | ||

| PTSD | ≥3 | 59 | ||

| Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, 10 items (AUDIT-10)[34] | Hazardous alcohol use | Community physicians’ offices, hospital-based clinics, and community health centers | ≥8 | 97 |

| Harmful alcohol use | ≥8 | 95 | ||

| Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test–Short Form (AUDIT-C),[30] 3 items | Hazardous drinkers | Primary care sample; measured against standardized interviews | ≥4 for men; ≥3 for women | 86 |

Abbreviations: CP=cut point, EHR=electronic health record, ER=emergency room, G/E=good or excellent, PTSD=post-traumatic stress disorder, SE=sensitivity, SCID=Structured Clinical Interview for DSM, SP=specificity.

The PHQ tools include screeners for depression (PHQ-9), somatoform disorders (PHQ-15), and anxiety disorders (GAD-7). While the PHQ also includes scales for alcohol use and eating disorders, these are not recommended for individual administration by the distributor.[41] The PSQ incorporates the AUDIT-10,[34] a validated tool for alcohol use problems. The PHQ-9, PHQ-15, GAD-7, and AUDIT-10 can be used independently or in combination.

Initial psychometric evaluations of the PHQ-9, PHQ-15, and GAD-7, compared against clinical interviews, showed good to excellent sensitivity and specificity for most DSM-5 disorders. However, the GAD-7 has only fair sensitivity for panic and social phobia and low sensitivity for post-traumatic stress disorder, indicating potential missed diagnoses. The PHQ-15 has fair specificity, which may lead to some false positives.

Three ultra-short tools derived from these instruments are the PHQ-4[30] (comprising the PHQ-2 and GAD-2), the PHQ-2[20, 21, 32] (depression screener), and the GAD-2[33] (anxiety screener), and the AUDIT-C[39] (alcohol problems). The PHQ-2, PHQ-4, and GAD-2 demonstrate sound psychometrics, though their sensitivity is generally lower than their specificity.

While PHQ and PSQ-based tools are somewhat limited in substance use disorder screening (AUDIT focuses solely on alcohol), they offer robust psychometrics and are highly applicable in primary care settings. A depression screening protocol might begin with the PHQ-2, followed by the PHQ-9 for those screening positive, although this sequential approach is not always consistently implemented.[42] Reviews of ultra-brief screens suggest the PHQ-2 is as effective as longer instruments, and its brevity and ease of administration make it a valuable primary care screening tool for mental health, particularly as a rule-out tool when follow-up resources are available.[9]

Additional Multiple-Disorder Screening Tools

Six additional multiple-disorder primary care screening tools for mental health were identified (Table 2). Two assess mental disorders, and five assess substance use disorders.

Table 2. Multiple-Disorder Screening Tools (Non-PHQ/PSQ) for Mental or Substance Use Disorders

| Scale | Target Conditions | Population and Gold Standard | Psychometrics | Application in Primary Care Practices |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP | SE (%) | |||

| Mental Disorders | ||||

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)[43] | Combined, 14 items | |||

| Anxiety (HADS-A), 7 items | Meta-analysis of studies | ≥8 | 80 | |

| Primary care patients; measured against CIS | ≥9 | 66 | ||

| Depression (HADS-D), 7 items | Meta-analysis | ≥8 | 80 | |

| Primary care patients; measured against CIS | ≥7 | 66 | ||

| Web-Based Depression and Anxiety Test (WB-DAT),[45] 11 gating questions and additional items depending on response | Major depressive disorder | Research subjects at clinical research center; measured against the SCID | 79 | |

| Panic disorder ± agoraphobia | 75 | |||

| Social phobia/social anxiety disorder | 74 | |||

| OCD | 71 | |||

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 63 | |||

| PTSD | 95 | |||

| Any anxiety disorder | 89 | |||

| Any disorder | 86 | |||

| Substance Use Disorders | ||||

| Kreek-McHugh-Schluger-Kellogg (KMSK) scale[46] | Combined, 28 items | Research volunteers in a genetics project; measured against the SCID | ||

| Opioids, 8 items | ≥9 | 100 | ||

| Cocaine, 7 items | ≥11 | 97 | ||

| Alcohol, 6 items | ≥11 | 90 | ||

| Simple Screening Instrument for Substance Abuse Potential (SISAP),[48, 49] 5 items | Overall risk of alcohol or drug dependence or abuse | Individuals with history of drug/alcohol use disorder; measured against the population-based NADS | ≥5 | 91 |

| Drug Abuse Screen Test (DAST-10),[50, 51] 10 items | Problems with drug use, not including alcohol or tobacco | Psychiatric outpatients with serious mental illness; measured against diagnosis of abuse or dependence | ≥3 | 85 |

| Tobacco, Alcohol, Prescription Medication and Other Substance Use (TAPS) tool,[53] 4 screener questions with up to 8 follow-up, depending on use | Alcohol | Primary care patients; measured against the CIDI with oral fluid testing | ≥1 | 74 |

| Prescription opioids | ≥1 | 71 | ||

| Heroin | ≥1 | 78 | ||

| Cocaine | ≥1 | 68 | ||

| Sedative | ≥1 | 63 | ||

| Marijuana | ≥1 | 82 | ||

| Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST),[55] 8 items | Global risk | One-third from specialty drug treatment settings and two-thirds from primary care settings in 7 countries around the world using discriminant validity between use and abuse; measured against ICE and MINI-Plus | >14.5 | 80 |

| Alcohol | >5.5 | 83 | ||

| Cannabis | >1.5 | 91 | ||

| Cocaine | >0.5 | 92 | ||

| ATS | >0.5 | 97 | ||

| Sedatives | >0.5 | 94 | ||

| Opioids | >0.5 | 94 | ||

| Global illicit | >6.5 | 88 |

Abbreviations: ATS=amphetamine-type stimulants, CIS=Clinical Interview Schedule, CP=cut point, G/E=good or excellent, ICE=Independent Clinical Evaluation, MINI-Plus=Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview-Plus, NADS=National Anti-Drug Strategy, OCD=obsessive-compulsive disorder, PHQ-9=9-item Patient Health Questionnaire, PTSD=post-traumatic stress disorder, SCID=Structured Clinical Interview for DSM, SE=sensitivity, CIDI=Composite International Diagnostic Interview, SP=specificity.

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)[43] and the Web-Based Depression and Anxiety Test (WB-DAT)[45] are designed to screen for multiple mental disorders, specifically depression and anxiety, which frequently co-occur. However, both tools have varying levels of sensitivity and specificity, and neither has been extensively validated in primary care settings. The HADS, originally developed for hospital settings, may not perform as effectively in primary care.[44] The WB-DAT, designed for web-based administration, allows for pre-visit screening but has limited psychometric validation in primary care.

Five tools screen for multiple substance use disorders. The KMSK scale[46] primarily quantifies substance use extent. The SISAP,[48, 49] DAST-10,[50, 51] TAPS tool,[53] and ASSIST[55] assess substance use-related problems. The DAST-10 and ASSIST demonstrate stronger psychometrics and have been more widely tested in primary care.

A trade-off exists between tool length and the specificity of problem identification. The DAST-10, with 10 items, broadly assesses consequences of drug use. The ASSIST, with eight questions across 10 drug categories, identifies specific substances causing issues but is complex to score in primary care settings.[58, 59]

Administration mode is crucial. Self-administered tools, like the DAST-10 (and a self-administered version of SISAP), may improve disclosure of sensitive information like illicit drug use.[60]

Additional Ultra-Short Screening Tools

Nine ultra-short (≤5 items) primary care screening tools for mental health not related to the PHQ family were identified (Table 3). Three screen for mental disorders, and six for substance use disorders. These tools can be combined for multi-condition screening.

Table 3. Ultra-Brief Single-Disorder Screening Tools

| Scale | Target Conditions | Population and Gold Standard | Psychometrics | Application in Primary Care Practices |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP | SE (%) | |||

| Mental Disorders | ||||

| Mental Health Inventory-5 items (MHI-5)[61] | Depression | Outpatient family medicine clinic; measured against the full PHQ battery | ≤4 | 88 |

| Anxiety | ≤4 | 100 | ||

| World Health Organization-Five Well-Being Index, 5 items (WHO-5)[63] | Depressive disorders | Primary care patients in 18 clinics; measured against the CIDI | 93 | |

| Brief Case-Find for Depression,[65] 4 items | Depression | Oncology patients; compared to the PRIME-MD | Yes to A or B AND Yes to C or D | 67 |

| Substance Use Disorders | ||||

| Cut down, Annoyed, Guilty, and Eye-opener[66] (CAGE), 4 items | Alcohol-related disorders | Primary care patients | ≥2 | 84 |

| Cut down, Annoyed, Guilty, and Eye-opener adapted for alcohol and drug use (CAGE-AID),[70, 71] 4 items | Risk of alcohol and drug abuse and dependence | Patients in family practice; measured against the DIS-R | ≥2 | 70 |

| Patients with schizophrenia and alcohol use | ≥1 | 91 | ||

| Two-Item Conjoint Screen (TICS)[72] | Substance use disorder | Primary care patients; measured against the CIDI | ≥1 | 80 |

| Single Question Screening Test for Drug Use,[73] 1 item | Current drug use (self-reported) | Primary care patients; measured against the DAST-10, the CIDI | ≥1 | 93 |

| Current drug use disorder | ≥1 | 100 | ||

| Current drug problem or drug use disorder | ≥1 | 94 | ||

| Current use (self-report or positive oral fluid test) | ≥1 | 85 | ||

| Current use (self-report or positive oral fluid test with drug problem or drug use disorder) | ≥1 | 85 | ||

| Single Alcohol Screening Question (SASQ),[74] 1 item | Unhealthy alcohol use | Primary care patients; compared with the AUDIT-C and calendar method collection of drinking days to establish risky drinking | ≥1 | 82 |

| Risky consumption amounts | ≥1 | 84 | ||

| Alcohol-related problems or disorder | ≥1 | 84 | ||

| Current alcohol use disorder | ≥1 | 88 | ||

| Fast Alcohol Screening Test (FAST),[75] 1 item initial screen; 4 total | Alcohol use disorder | Primary care patients | ≥3 | 91 |

Abbreviations: AUDIT=Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, AUDIT-C=Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test–Short Form, CP=cut point, DAST-10=Drug Abuse Screen Test, DIS-R=Diagnostic Interview Schedule-Revised, G/E=good or excellent, PHQ-9=9-item Patient Health Questionnaire, SE=sensitivity, SP=specificity.

The MHI-5,[61] WHO-5,[63] and Brief Case-Find for Depression[65] are ultra-short mental disorder tools. The Brief Case-Find was designed for medically ill populations. These tools generally have weaker sensitivity and specificity than the PHQ-4.

The CAGE,[66] for alcohol-related disorders, has strong psychometrics but lower sensitivity in women at the traditional cut-off of 2.[67] The CAGE-AID[70, 71] screens for both alcohol and drugs with variable sensitivity and specificity across cut-offs and populations.

Choosing between tools like the CAGE and AUDIT-C (both for alcohol problems) requires understanding their focus. The AUDIT-C screens for less severe issues like risky drinking, while the CAGE targets lifetime and current alcohol abuse or dependence.[8] Population differences also matter; for example, the AUDIT-C requires lower thresholds for women due to metabolic differences in alcohol processing.[39, 77]

Four ultra-brief, one-item substance use disorder screens were identified: Single Question Screening Test for Drug Use, Single Alcohol Screening Question, TICS, and FAST.[72–75, 78] These generally show strong psychometrics. However, conjoint screens do not differentiate between the type or severity of substance use disorders.[70, 78]

Discussion

This review provides a synthesis of the literature on primary care screening tools for mental health, emphasizing the psychometric properties of publicly available instruments for common behavioral health disorders in primary care. It identified 24 tools, including 13 brief instruments with five or fewer items. Tool selection is complex and practice-specific, requiring PCPs to balance psychometrics with factors like prevalent conditions, staffing, reimbursement, quality measures, follow-up availability, and PCP familiarity with behavioral health. This review aims to support informed tool selection, considering these diverse factors.

Factors in Screening Tool Selection: Measurement

The debate between longer, multiple-disorder tools and shorter, single-disorder scales for mental health screening continues.[79] Multiple-disorder tools (e.g., WB-DAT, DAST-10, ASSIST) may be lengthy and complex but can uncover a broader range of behavioral health issues and psychological functioning than single-disorder tools.[33, 80]

Shorter, single-disorder tools offer flexibility to target prevalent conditions and create tailored, brief screening protocols. However, assessing conditions in isolation may miss co-occurring disorders, which are common.[81] Combining single-disorder tools can also introduce context effects and potentially alter psychometric properties if not administered as part of a larger instrument like the PHQ or PSQ.

This review has limitations. While the search strategy captured well-known tools like the PHQ, the focus on common disorders and the continuous development of new tools mean some tools might have been missed. Not every study for each tool was included, potentially overlooking subgroup-specific psychometric data. Finally, the review prioritized breadth over in-depth analysis, not rigorously assessing the methodological quality of psychometric testing or fine distinctions between similar screeners.

Factors in Screening Tool Selection: Primary Care Considerations

Tool selection must consider the clinic’s patient population. Practices with high rates of co-occurring behavioral health conditions might favor PHQ and PSQ-derived tools, which can be combined to address common conditions. The PHQ-9 is endorsed by the National Quality Forum[82] and is reimbursable by Medicare, Medicaid, and some commercial insurers (though diagnostic follow-up is crucial).[83] Clinics serving seriously ill outpatients might consider tools developed for physically ill populations (e.g., HADS).

Choosing between shorter and longer tools requires balancing time constraints and patient population characteristics. Web-based tools like WB-DAT suit fast-paced, understaffed clinics but not those serving patients with low literacy. Conjoint screens (e.g., CAGE-AID, TICS) are useful for general population clinics with low positive screen rates but may be insufficient in settings with high polysubstance use, where separate alcohol and drug screens (e.g., ASSIST) might be preferred to streamline referral processes.[70, 78]

Psychometrics must be interpreted in the context of the patient population and available follow-up. Ultra-short screens with high specificity are best for ruling out disorders[15]; negative results are reliable indicators of the absence of a disorder, reducing unnecessary follow-up. However, low sensitivity can lead to false negatives and missed cases. Clinics with generally healthy populations and sufficient follow-up capacity for false positives might use highly sensitive tests followed by specific confirmatory tests.

High sensitivity screens are appropriate for practices with higher behavioral health needs and resources for rapid diagnostic assessment. These screens increase the likelihood of identifying true positives, important in populations with many subthreshold cases.

Crucially, practices need a plan for patients who screen positive.[84] Follow-up can include in-practice treatment or referral to specialists. Practices with readily available behavioral health clinicians may prefer broad, multi-problem tools. Others might start with screening for specific conditions, expanding protocols as referral networks grow.

Many primary care practices already have physical health screening protocols and can integrate primary care screening tools for mental health into existing workflows. Implementing enhanced behavioral health screening may require practice changes like training and workflow adjustments. Effective recognition and management of behavioral health conditions are vital in the evolving value-based healthcare system. Future research should focus on successful screening implementation and sustainable payment models.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The views and opinions expressed and the content of the study are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, or policies of SAMHSA or HHS. We acknowledge Dr. Whitney Witt’s expert input on the study design and Dr. Ali Bonadkir Tehrani’s technical support.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.