1. Introduction

1.1. The Growing Need for Geriatric Oral Health Focus

The global population is aging at an unprecedented rate. Projections indicate that by 2030, approximately 1.4 billion individuals will be 60 years or older, a number expected to surge to 2.1 billion by 2050 [1]. This demographic shift presents significant healthcare challenges, particularly concerning the oral health of older adults, a domain often overshadowed by other health concerns yet profoundly impactful on overall well-being and quality of life [2, 3]. Older adults, especially those aged 65 and above, are susceptible to a spectrum of oral health issues, ranging from untreated dental caries and periodontal diseases to complete tooth loss and oral cancer [4, 5, 6]. For instance, in regions like Hong Kong, a considerable percentage of older community-dwelling individuals experience complete edentulism, often linked to economic factors favoring tooth extraction over restorative treatments [6]. Alarmingly, a significant majority of older adults, particularly those in long-term care institutions (LTCIs), do not engage in routine annual dental check-ups unless prompted by acute oral health problems [2, 6].

The state of oral health in older populations is intrinsically linked to their general health status, with poor oral health acting as a significant contributor to increased morbidity and mortality [7]. Specifically, poor oral health is implicated in the pathogenesis and progression of various non-communicable diseases, including diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, chronic respiratory conditions, nutritional deficiencies, arthritis, and neurodegenerative disorders [5, 6, 7, 8, 9]. The Global Burden of Disease study in 2017 highlighted the substantial role of oral disorders in causing disabilities among individuals aged 50–74 worldwide [10]. Developing countries often report higher prevalences of dental problems in older populations [11]. Research in Hong Kong has revealed that older adults aged 65–74 frequently suffer from multiple oral health issues such as dental and root caries, gingival bleeding, and periodontitis [12]. These conditions can lead to functional impairments like difficulties in eating, chewing, and speaking, as well as nutritional deficits, collectively diminishing oral health-related quality of life and overall health [8, 9, 13]. It is crucial to recognize that poor oral health in the elderly disproportionately affects vulnerable groups, including those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, lacking dental insurance, and ethnic minorities, exacerbating the complexities of access to and utilization of dental and general healthcare services for prevention and treatment of oral health problems [1, 2, 14].

Recognizing the critical need for proactive oral health management in older populations, various countries have implemented policies aimed at enhancing oral health services for older adults both in community settings and LTCIs. Examples include Australia’s provision of subsidized public dental care and assignment of oral health therapists to LTCIs for low-income older adults [15]. Japan has integrated oral health services into its medical insurance system to cater to the needs of older adults. In the United Kingdom, guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) emphasize the importance of maintaining and improving the oral health of residents in care homes [16]. Similarly, Hong Kong has launched several oral and dental health promotion programs, including healthcare vouchers for dental consultations and the Community Care Fund Elderly Dental Assistance Program [17]. Despite these initiatives, older adults residing in LTCIs remain particularly vulnerable to poor oral health due to physical limitations and increased dependence on others for care [4, 5, 18], exhibiting significantly worse oral health compared to their community-dwelling counterparts [4, 12, 19]. This disparity is often attributed to inadequate self-care practices and insufficient or ineffective oral care assistance provided by healthcare workers [20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25].

A key factor contributing to the compromised oral health of older adults in LTCIs is the potential lack of adequate knowledge, positive attitudes, and effective practices (KAP) among healthcare workers regarding oral care [26]. While educational interventions have been designed to improve healthcare workers’ oral care knowledge and skills, their impact on actual oral healthcare delivery has been inconsistent. A study investigating the effectiveness of an educational program in LTCIs showed that while healthcare workers’ knowledge improved, the oral health of residents remained poor even after care provided by these trained workers. Common issues observed included poor oral hygiene, tooth fractures, periodontal disease, food impaction, and halitosis. These findings underscore that insufficient oral health assessments and suboptimal oral care techniques are significant contributors to poor oral health in older residents.

Oral health assessments are paramount for early identification of problems and prevention of severe oral and systemic health conditions [27]. Tools like the widely used Oral Health Assessment Tool (OHAT) are valuable for screening oral health across multiple domains, including soft tissues, saliva, teeth, dentures, oral hygiene, and pain [28]. However, effective use of OHAT requires specialized training, which healthcare workers in LTCIs may lack. Therefore, a simplified, user-friendly oral health assessment tool is essential for these settings [27]. Although various oral care checklists exist, a validated assessment tool specifically tailored for healthcare workers in LTCIs has been lacking. Such a tool is crucial to standardize and enhance the quality of oral health assessments and oral care procedures for older residents in these institutions.

This study addresses this critical gap by aiming to develop and validate an Oral Health Assessment Tool For Long Term Care settings. The goal is to create a practical tool that can guide and evaluate healthcare workers’ oral care practices, ultimately improving the oral health outcomes of older residents. Upon validation, this tool is intended for routine use by healthcare workers in LTCIs to ensure comprehensive and consistent oral health assessments and care procedures. By providing clear guidance on proper assessment and care, this tool can significantly contribute to better oral and overall health for older adults in long-term care.

1.2. Operational Definitions (Omitted for brevity and relevance to the target audience)

1.3. Study Aim

This study aimed to develop and validate an assessment tool to improve current oral care practices delivered by healthcare workers and enhance the oral health of older residents in long-term care institutions (LTCIs).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study employed a five-step tool validation procedure to assess the content validity of the developed oral health assessment tool for long term care. The steps included: (1) initial tool development in the native language based on literature review, (2) translation and back-translation, (3) expert consultations, (4) pilot study for validation, and (5) finalization of the assessment tool [29, 30, 31].

2.2. Literature Review

A comprehensive literature review formed the basis for the preliminary oral health assessment tool. The review aimed to identify factors influencing effective oral care procedures and ensure the tool addressed potential errors and promoted best practices. Inclusion criteria for studies were: publication between 2013 and 2023, primary studies evaluating oral health or care practices, focus on older adults or LTC residents, available abstracts, and English or Chinese language. Exclusion criteria included clinical guidelines, editorials, and expert opinions.

Databases searched included PubMed, MEDLINE (OvidSP), and CINAHL, using keywords related to “oral health”, “oral care”, “assessment”, “checklist”, “elderly”, “long-term care”, and related terms in both English and Chinese. Google Scholar and reference lists of relevant articles were also searched. Two independent reviewers screened articles, with a third reviewer resolving disagreements.

2.3. Two-Stage Expert Consultation

Two rounds of expert consultation were conducted to refine the assessment tool. The first consultation involved at least six experts who independently reviewed the tool’s format, rating methods, and items, providing feedback on accuracy, relevance, and completeness of both oral health assessment and oral care procedure components [32]. The tool was revised based on this feedback.

The second consultation involved another panel of six experts in a formal discussion to finalize the assessment tool.

2.4. Tool Translation and Interviews (Interviews section likely refers to language reviewers, clarified below)

Based on the literature review and first expert consultation, relevant assessment items were identified. A preliminary oral health assessment tool for long term care was developed in both English and Chinese. The tool underwent rigorous translation and back-translation processes to ensure linguistic accuracy. Two language reviewers, native speakers of English and Chinese proficient in both languages, approved the final versions [33]. The term “interviews” in the original heading likely refers to discussions with these language reviewers to ensure semantic equivalence across languages.

2.5. Content Validity

During the second expert consultation, content validity was rigorously assessed. Experts evaluated each item’s appropriateness, structure, clarity, and ambiguity using the Content Validity Index (CVI) and Content Validity Ratio (CVR). CVR measured item essentiality, while CVI assessed item relevance and clarity [34, 35, 36].

Experts rated item relevance on a four-point scale (1=not relevant to 4=highly relevant). Items rated below 3 were revised. Item-level CVI (I-CVI) and scale-level CVI (S-CVI) were calculated. I-CVI values above 0.79 indicated relevance, 0.7-0.79 required revision, and below 0.7 indicated elimination [34]. S-CVI, calculated using both Average CVI (A-CVI) and Universal Agreement (UA) methods, assessed overall content validity, with S-CVI/UA of 0.8 or greater considered excellent [35, 36]. CVR was calculated using the formula: CVR = (Ne − N/2)/(N/2), where Ne is the number of experts rating an item as ‘essential’, and N is the total number of experts [35].

2.6. The Pilot Study

A pilot study was conducted to assess the tool’s reliability, applicability, and feasibility in a real-world setting. Concurrent reliability was tested by evaluating agreement between two assessors. Face validity, practicality, and feasibility were assessed using experienced nurse assessors and educators. Assessors evaluated the tool’s comprehensiveness, clarity, logical organization, and ease of understanding and acceptance [37, 38]. The pilot study aimed to identify and address potential issues before broader implementation.

Participants, 20 nursing students who had completed oral care training or healthcare workers with oral care responsibilities, were recruited using purposive and convenience sampling. They performed oral health assessments and care procedures in a laboratory setting. Assessors used the oral health assessment tool for long term care to document performance and gather feedback for refinement.

Pilot Study Procedure

Following ethical approval, participants provided informed consent and were paired to perform oral health assessments and oral care procedures on each other in 30-minute sessions. The principal investigator (PI) and co-investigator (Co-I) acted as independent assessors using the developed tool. Agreement between assessors was evaluated to ensure assessment consistency and item appropriateness. Participant feedback was also collected to identify areas for improvement. Data collection continued until the tool was finalized, and no further modifications were deemed necessary. The finalized tool was then reviewed by experts from the second consultation.

2.7. Assessment Tool Finalisation

Following the pilot study and incorporation of feedback, the oral health assessment tool for long term care underwent a final refinement process to ensure accuracy, appropriateness, and clarity of all items. This step ensured the tool was ready for implementation in LTC settings to effectively assess oral health and oral care procedures.

2.8. Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Tung Wah College Research Ethics Committee (REC2023179). All participants provided informed consent, and data confidentiality was maintained through encryption and restricted access to the research team.

3. Results

3.1. Content, Domain Specification, and Item Generation

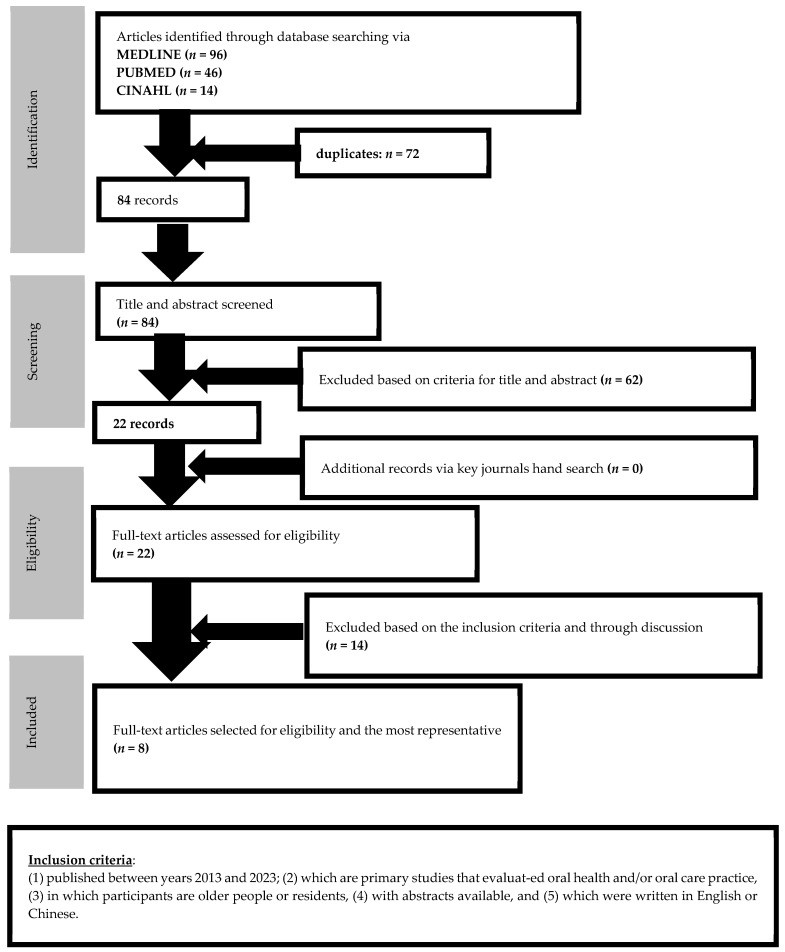

The literature review process, illustrated in Figure 1, initially identified 156 articles from MEDLINE, PubMed, and CINAHL databases. After removing duplicates and screening for relevance and eligibility, 8 quantitative studies were selected for in-depth review to inform the development of the oral health assessment tool for long term care.

Figure 1. Flow of searching and Inclusion of relevant articles.

The developed assessment tool comprises two parts: Part I for oral health screening and Part II for oral care procedure assessment, both in English and Chinese. Part I, designed for LTC residents, was informed by existing tools like the Oral Health Assessment Tool (OHAT) and the Kayser-Jones Brief Oral Health Status Assessment (BOHSE). The development team (WKL and FMFW) adapted items from OHAT and BOHSE, focusing on relevance for LTC healthcare workers and essential oral health screening aspects. Part I includes assessments of lips, oral mucosa, teeth, tongue, and related conditions. It recommends reporting and dental consultation for any observed abnormalities (pain, color changes, dryness, swelling). Part II focuses on systematic assessment of oral care procedures, serving as a checklist to guide healthcare workers and facilitate self-evaluation and training. This section complements Part I by ensuring both assessment and proper care are addressed.

3.2. Two-Stage Expert Review

Two expert reviews validated the tool’s applicability and appropriateness. In the first review, six experts (dentists, geriatric nurse, nurse educator, dental hygienists) reviewed English and Chinese drafts, providing feedback via email or phone. Modifications were made to enhance alignment with essential criteria for assessing oral health in older residents and current best practices for oral care procedures. For example, infection control measures were moved to the beginning of the checklist, and items on lighting and safety were emphasized based on expert feedback.

The second review involved another panel of six experts (community dentist, geriatric nurse, nurse educator, dental nurses, residential home nurse) who independently evaluated the tool. They assessed appropriateness, structure, clarity, and ambiguity using CVI. CVR scores indicated item essentiality. Experts rated all 23 items (7 oral health assessment, 16 oral care procedures) as highly relevant (scores 3-4). Narrative feedback led to further refinements, such as changing “whiteness” to “pale” for describing lip and mucosa color and adding items related to oral hygiene conditions (food debris, bad breath) to Part I, as suggested by the residential home nurse.

All six experts rated all items as ‘very relevant,’ resulting in an I-CVI score of 1.0 for each item and a CVR of 1.0, indicating excellent agreement on relevance and clarity. The S-CVI/UA was also excellent, with all experts rating all items as ‘very relevant’. The developed oral health assessment tool for long term care demonstrated excellent content validity. (See Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 for detailed expert review results).

3.3. Tool Refinement

A Delphi method with two evaluation rounds was employed for tool refinement [35]. The first round focused on clarity, sequencing, and eliminating redundancy. Five items in Part I and eight in Part II were rephrased. One and three items were added to Parts I and II, respectively. Two items in Part II were repositioned for better procedural flow. After CVI calculations and cognitive interviews, the final tool version included 21 items (see Supplementary Table S1).

3.4. The Pilot Study

The pilot study assessed the applicability and feasibility of the oral health assessment tool for long term care. Twenty nursing students or enrolled nurses with oral care training participated (40% female, mean age 24.2 years). All had at least one year of oral assessment and care procedure training.

Participants performed oral health assessments and oral care procedures on each other. Beforehand, they received Parts I and II for preparation. Two independent assessors evaluated all procedures, categorizing performance as ‘unsatisfactory’, ‘satisfactory’, or ‘not done’.

Post-procedure, participants provided feedback. Four participants suggested adding a ‘normal’ condition option to Part I, which was implemented. A footnote was added to the denture assessment for clarity on denture use and fit. A description for Item 9 in Part II was added to clarify denture cleaning instructions. Assessors recommended adding two items to Part II: ‘Maintain communication with the older resident during the procedure’ and ‘Provide brief education and/or oral condition information to the older resident after the procedure.’ These enhancements finalized the assessment tool (Supplementary Table S3).

4. Discussion

Older residents in LTCIs often experience poorer oral health due to factors such as reduced self-care ability and inadequate oral health assessment and care by healthcare workers [26]. This is a significant concern as poor oral health can exacerbate other health issues, including non-communicable diseases and nutritional deficiencies [5, 8, 9]. Therefore, it is crucial to ensure healthcare workers are well-trained, guided, and monitored in providing oral health assessment and care.

This study successfully developed an oral health assessment tool for long term care with two distinct sections tailored for healthcare workers in LTCIs. The study focused on establishing the content validity and applicability of the tool’s items through literature review and expert consultation [35, 36]. The tool underwent rigorous refinement through expert reviews, modifications, and pilot testing. Part I comprehensively assesses residents’ oral health, while Part II provides a systematic procedure for oral care.

Expert input from dental and nursing professionals was instrumental in ensuring the tool’s accuracy, relevance, applicability, and feasibility for healthcare workers. Content validity, as confirmed by high I-CVI, S-CVI, and S-CVI/UA scores, demonstrates that the tool’s items are relevant and clear [34, 35]. The tool facilitates effective oral condition assessment and emphasizes the importance of documenting and reporting any abnormalities for timely dental consultation.

The pilot study, involving nursing students with oral care training, was critical for validating the tool’s applicability and feasibility [35, 37]. Feedback from participants and assessors led to practical improvements, enhancing the tool’s user-friendliness and relevance to the LTC context. The involvement of two independent assessors further strengthened the tool’s reliability. The tool is designed for efficient use, with an estimated completion time of approximately 10 minutes.

The integration of oral health assessment (Part I) with oral care procedure (Part II) in this tool is a key strength, prompting healthcare workers to consistently perform both components. This integrated approach serves as a valuable guide, providing step-by-step instructions for oral care and emphasizing crucial precautions like infection control.

The finalized oral health assessment tool for long term care, developed through expert consensus and pilot testing, aims to enhance healthcare workers’ confidence and competence in providing oral care to older residents. It can serve as both a self-evaluation checklist and a tool for regular performance assessments in training and practice. Addressing any performance deficits identified by the tool is crucial for safeguarding residents’ oral health. Healthcare workers with consistently unsatisfactory ratings should participate in targeted oral health training programs.

The interconnected nature of the assessment and procedure sections underscores the importance of conducting oral health assessments during oral care procedures. This integration helps identify dental needs and assess residents’ abilities to manage daily oral care [27].

While designed for LTCIs, this tool can be adapted for use in various clinical and community settings. Training on effective oral health assessments and care procedures is essential for all healthcare providers involved in caring for individuals unable to perform self-care [27].

The development of this oral health assessment tool for long term care aligns with the increasing emphasis on geriatric oral health. Initiatives like Hong Kong’s Outreach Dental Care Programme highlight the need for effective tools to identify and address oral health problems in LTCIs [5, 39]. Regular use of this validated tool is crucial for identifying oral health issues and facilitating timely interventions. Furthermore, adequate resources should be allocated to oral health training for healthcare workers, and LTC management should ensure consistent and proper implementation of oral health assessments and care procedures. Integrating this assessment tool into daily practice can significantly contribute to maintaining and improving the oral health of older residents in LTCIs.

4.1. Future Directions for Research and Tool Refinement

Future research should focus on further validation of oral health assessment tools for long term care, particularly for denture-related issues and oral health complication risks. Customizing the tool based on resident care dependency levels is also essential to address diverse needs and challenges. Adapting tools to different care settings and contexts is crucial for broader applicability. Comparative studies of existing tools can guide ongoing refinement and development of more comprehensive assessment methods. Longitudinal studies with larger samples of healthcare workers are needed to evaluate the long-term impact of oral care practices and tool effectiveness on resident oral health outcomes.

Exploring technology integration, such as mobile apps or wearable devices for real-time data collection and personalized feedback, could further enhance assessment accuracy and efficiency. Interdisciplinary collaboration with dental, geriatric, and nursing professionals is vital for comprehensive evaluation and improvement of oral health and care practices. Standardizing assessment tools and protocols across healthcare settings will enable data comparability, research collaboration, and promote evidence-based oral care practices.

4.2. Strengths and Weaknesses

This study’s key strength is the development and validation of a specific oral health assessment tool for long term care, addressing a gap in existing tools by focusing on the unique needs of older residents in LTCIs. The tool provides a systematic approach to enhance daily oral care practices and improve oral health outcomes. Its benefits extend to various healthcare professionals and caregivers involved in older adult care, offering a standardized and comprehensive approach to assessment and training.

A limitation is the absence of direct participation from older residents in the study due to practical and ethical constraints. Future studies should include older residents to further validate the tool and ensure it accurately captures their specific oral care needs and experiences. While designed for older populations, modifications and revalidation may be required for use in other demographics. Factor analysis was not feasible due to the pilot study’s sample size; larger studies with more healthcare workers are needed for more robust validation.

5. Conclusions

This newly developed oral health assessment tool for long term care represents a significant advancement in geriatric oral health. As the first tool integrating both oral health and oral care procedure assessments, its development involved a rigorous process of literature review, expert consultation, refinement, and pilot validation. The tool demonstrates high content validity and applicability across clinical and community settings, not limited to LTCIs. Its versatility makes it valuable for both research and practice, with the potential to significantly improve oral health outcomes for older populations. It also serves as a valuable instrument for staff training and performance evaluation. The oral health assessment form and oral care procedure checklist provide structured guidance for healthcare workers, enhancing the quality of oral care and overall well-being of older residents. Successful implementation requires government support and resource allocation for oral health training to optimize oral health outcomes and improve the quality of life for older adults.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to the students in the Higher Diploma in Nursing and Bachelor of Health Science (Major in Nursing) (Hon) programs for their invaluable support and participation in the pilot study.

Supplementary Materials

The following supplementary materials are available online at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/healthcare12050558/s1, Table S1: Expert review results for relevancy check and comments, Table S2: The CVI and CVR results, Table S3: Assessment tool for oral health and oral care procedures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.M.F.W.; methodology, F.M.F.W.; validation, F.M.F.W. and A.W.; formal analysis, F.M.F.W.; investigation, F.M.F.W.; resources, F.M.F.W.; data curation, F.M.F.W. and A.W.; writing—original draft preparation, F.M.F.W.; writing—review and editing, F.M.F.W., A.W., and W.K.L.; visualization, F.M.F.W., A.W., and W.K.L.; supervision, F.M.F.W.; project administration, F.M.F.W. and A.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Tung Wah College (ethics application number: REC2023179 and 11 October 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to participants’ confidentiality.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

[List of References – Same as original article]

Associated Data

Supplementary Materials

healthcare-12-00558-s001.zip (112.5KB, zip)

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to participants’ confidentiality.