Introduction

Cancer and its treatments often lead to a significant decline in patients’ quality of life (QoL), marked by fatigue, reduced physical fitness, and symptoms of anxiety and depression. Recognizing the beneficial impacts of exercise during and after cancer treatment on QoL is crucial. While numerous studies have highlighted these benefits, understanding how exercise improves QoL from the patient’s perspective remains vital for optimizing care and adherence. This study delves into patient experiences using concept mapping, a tool for improving patient care by structuring and objectifying rich qualitative data. By employing this innovative methodology, we aim to uncover the nuanced ways in which supervised exercise programs contribute to the enhanced well-being of cancer patients. This insight is essential for healthcare providers to better understand and address patient needs, ultimately leading to improved referral, participation, and adherence to exercise interventions.

Concept Mapping Methodology for Patient-Centered Care Improvement

This research utilized concept mapping, a mixed-methods approach that combines group processes with statistical analysis, to investigate patient perspectives. This methodology is particularly valuable as concept mapping is a tool for improving patient care by providing a visual and structured framework of patient-generated ideas. Our study involved patients with cancer participating in supervised exercise programs. The process began with brainstorm sessions where patients responded to the focus statement: “How has participating in a supervised exercise program contributed positively to your quality of life?” Following these sessions, patients individually clustered similar ideas and rated their importance online. This data was then synthesized to create a concept map, visually representing the interconnected themes of how patients perceive exercise enhances their QoL. The research team further analyzed these clusters, and physiotherapists provided practical insights through semi-structured interviews, grounding the patient-generated concepts in clinical reality.

Key Patient-Reported Benefits Identified Through Concept Mapping

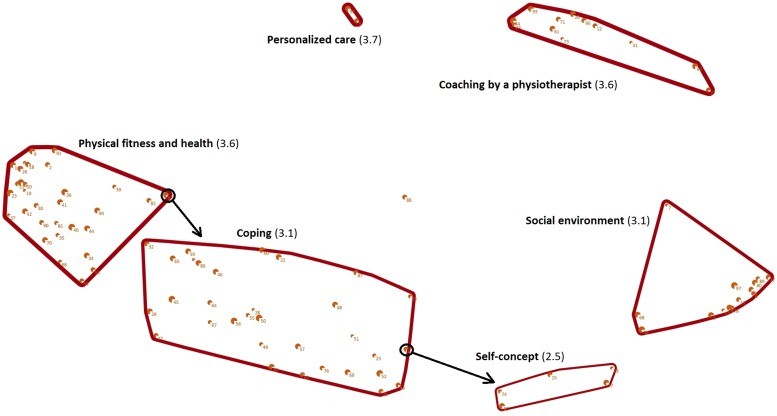

Sixty patients participated in the brainstorm sessions, generating a wealth of ideas. Forty-four patients completed the online clustering and rating, culminating in a concept map that revealed six key clusters of benefits: personalized care, coaching by a physiotherapist, social environment, self-concept, coping, and physical fitness and health. Notably, personalized care emerged as the most important factor in improving QoL through exercise. The physiotherapists interviewed largely validated these clusters, confirming their relevance in clinical practice.

Concept map of patients perspectives of how supervised exercise programs during or following cancer treatment improves their quality of life: cluster name (rate of importance). Note that each point on the concept map represents one of the ideas that the patients generated in response to the focus statement. Points closer to each other were clustered more often together by the patients and are therefore related. The number of each point corresponds to the ideas presented in Table 2. The size of each point represents the mean rate of importance of the corresponding idea, with a larger point indicating a higher mean rate of importance. The line width of a cluster represents the mean rate of importance of all the ideas included in the corresponding cluster, with thicker lines representing a higher mean rate of importance. The arrows represent the ideas that were relocated by the researchers.

Concept map of patients perspectives of how supervised exercise programs during or following cancer treatment improves their quality of life: cluster name (rate of importance). Note that each point on the concept map represents one of the ideas that the patients generated in response to the focus statement. Points closer to each other were clustered more often together by the patients and are therefore related. The number of each point corresponds to the ideas presented in Table 2. The size of each point represents the mean rate of importance of the corresponding idea, with a larger point indicating a higher mean rate of importance. The line width of a cluster represents the mean rate of importance of all the ideas included in the corresponding cluster, with thicker lines representing a higher mean rate of importance. The arrows represent the ideas that were relocated by the researchers.

These findings underscore that supervised exercise programs offer multifaceted benefits beyond physical improvements. Patients reported enhancements in social, mental, and cognitive well-being, all contributing to their improved QoL. This concept map serves as a powerful visual representation of patient perspectives, highlighting the key areas to focus on in exercise programs for cancer patients.

Leveraging Concept Mapping to Enhance Patient Care in Exercise Programs

The cluster of physical fitness and health aligns with previous quantitative research demonstrating the role of improved fitness in mediating the positive effects of exercise on QoL. However, this study, through concept mapping as a tool for improving patient care, goes further by revealing the significant impact of psychosocial factors. The clusters of social environment, self-concept, and coping highlight the importance of these less tangible aspects. While self-efficacy, a known mediator, wasn’t explicitly identified as a cluster, it is likely interwoven with the ideas within the self-concept cluster. Interestingly, while distress reduction is often cited, it was not directly mentioned by patients as a primary factor in QoL improvement in this study. This may suggest that patients either did not perceive distress as a separate construct or that distress reduction was implicitly included within their broader understanding of QoL.

The primary goals of supervised exercise interventions are indeed to maintain or improve physical strength and fitness. The clusters of physical fitness and health, personalized care, and physiotherapy coaching directly reflect these objectives. However, the study’s concept map expands this understanding by emphasizing the crucial role of social environment, coping mechanisms, and self-concept in enhancing patient QoL. These patient-identified experiences resonate with findings from other qualitative studies that point to benefits like positive distraction, social support, and enhanced self-efficacy. Concept mapping, as a tool for improving patient care, provides a structured way to validate and prioritize these patient-centered experiences.

Practical Applications of Concept Mapping for Better Patient Outcomes

This study reinforces that exercise positively influences not only physical health but also the social, mental, and cognitive dimensions of health, all of which contribute to QoL. This holistic view of health aligns with previous research involving patients, healthcare providers, and policymakers. The concept map generated in this study acts as a valuable conceptual framework, visualizing patient perspectives and serving as Concept Mapping A Tool For Improving Patient Care. By understanding these patient-prioritized constructs, healthcare professionals can enhance awareness among both physicians and patients regarding the importance of supervised exercise programs during and after cancer treatment. This enhanced awareness can lead to improved referral rates, greater patient participation, and better adherence to these beneficial programs.

Furthermore, the insights gleaned from this concept mapping study can directly inform the optimization of supervised exercise programs. By focusing on personalized care, the supportive coaching of physiotherapists, fostering a positive social environment, and addressing self-concept and coping strategies, programs can be tailored to better meet the holistic needs of cancer patients. Future research should further investigate the mediating role of these psychosocial constructs in the relationship between exercise and QoL to solidify these findings and refine intervention strategies.

The Value and Considerations of Concept Mapping in Patient Care Research

This study stands out as the first to utilize concept mapping to specifically explore patient perspectives on how exercise improves QoL during or after cancer treatment. Concept mapping, as a tool for improving patient care, empowers patients to contribute uniquely to research, and its sophisticated statistical analysis allows for the visualization and interpretation of large datasets of qualitative patient data. The resulting concept map offers a powerful and accessible way to understand the collective perspectives of a diverse group of patients, thereby advocating for the wider adoption and recognition of exercise programs as a vital component of cancer care and QoL enhancement.

Despite its strengths, there are limitations to consider. The study’s focus statement was intentionally framed to explore the positive impacts of exercise. While this approach yielded valuable insights into benefits, it did not capture potential negative experiences. Additionally, the study population was predominantly women with breast cancer, and most were undergoing treatment with curative intent. Further research is needed to determine if these findings are generalizable across different cancer types, stages, and patient populations. Software limitations required the merging of some ideas, potentially leading to overly broad or slightly ambiguous statements. Finally, some patients reported difficulties with the online clustering and rating process. Future studies could consider incorporating face-to-face sessions or paper-based methods for these tasks to enhance accessibility and support for all participants.

Conclusion: Concept Mapping as a Catalyst for Patient-Centered Improvements in Cancer Care

In conclusion, this study, employing concept mapping a tool for improving patient care, demonstrates that supervised exercise programs significantly contribute to the quality of life of cancer patients by improving physical fitness and health, and crucially, by providing personalized care, expert physiotherapy coaching, a supportive social environment, and enhancing self-concept and coping abilities. These findings highlight that cancer rehabilitation programs improve QoL through a multifaceted approach that extends beyond physical improvements to encompass social, mental, and cognitive well-being. By understanding the broad spectrum of factors that influence QoL, healthcare providers can better inform patients and other stakeholders about the profound potential of exercise during and after cancer treatment to enhance QoL, ultimately fostering improved patient referral, awareness, and sustained engagement with exercise programs.

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the executive committee of OncoNet (http://www.onconet.nu) for inviting physiotherapists to collaborate with our study and thank all the patients and physiotherapists who participated.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Maike G. Sweegers, Laurien M. Buffart, Johannes Brug, Mai Chin A Paw, Teatske M. Altenburg

Provision of study material or patients: Maike G. Sweegers, Wouke M. van Veldhuizen, Edwin Geleijn

Collection and/or assembly of data: Maike G. Sweegers, Laurien M. Buffart, Wouke M. van Veldhuizen, Edwin Geleijn, Teatske M. Altenburg

Data analysis and interpretation: Maike G. Sweegers, Wouke M. van Veldhuizen, Henk M.W. Verheul, Johannes Brug, Mai Chin A Paw, Teatske M. Altenburg

Manuscript writing: Maike G. Sweegers, Laurien M. Buffart, Wouke M. van Veldhuizen, Edwin Geleijn, Henk M.W. Verheul, Johannes Brug, Mai Chin A Paw, Teatske M. Altenburg

Final approval of manuscript: Maike G. Sweegers, Laurien M. Buffart, Wouke M. van Veldhuizen, Edwin Geleijn, Henk M.W. Verheul, Johannes Brug, Mai Chin A Paw, Teatske M. Altenburg

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

[1] Berger AM, Mooney K, Alvarez-Perez A, et al. Cancer-related fatigue, version 2.2015. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13(8):1012-1039.

[2] Servaes P, Verhagen C, Bleijenberg G. Fatigue in cancer patients during and after treatment: a systematic review of instruments and interventions. Cancer Treat Rev. 2002;28(6):389-401.

[3] Hofman M, Ryan JL, Figueroa-Moseley CD, et al. Cancer-related fatigue: the need for valid and reliable assessment and research-based interventions. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57(3):147-161.

[4] Jones LW, Alfano CM. Exercise-oncology research: past, present, and future. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2011;21(2):161-167.

[5] Calsius J, Berger J, Hartmann M, et al. Physical activity and cancer. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108(25):435-442.

[6] Ganz PA. Cancer-related fatigue: emerging insights and therapeutic strategies. Oncology (Williston Park). 2007;21(12 suppl 8):10-21.

[7] Speck RM, Courneya KS, Mâsse LC, Duval S, Schmitz KH. An update of controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4(2):87-100.

[8] McNeely ML, Campbell KL, Rowe V, et al. Systematic review of exercise interventions to improve cancer-related fatigue in adults treated with chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Cancer Treat Rev. 2006;32(7):495-513.

[9] Galvão DA, Taaffe DR. Exercise in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of exercise during and after cancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55(3):158-189.

[10] Fong DK, Ng AV, Johnston MF, et al. Exercise intervention for cancer-related fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:522.

[11] Mishra SI, Scherer RW, Geigle PM, et al. Exercise interventions on health-related quality of life for cancer survivors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8:CD007566.

[12] Courneya KS, Friedenreich CM, Sela RA, McGrath ER, Lakoski SG, Woolcott CG, Hayden JA, Jones LW, Johnston MF, Yasui Y, McKenzie DC. Exercise and quality of life in colorectal cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(23):4396-4404.

[13] van Waart H, Stuiver MM, van Harten WH, et al. Effect of exercise training during adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer on physical and mental health. Cancer. 2010;116(18):4083-4093.

[14] Mock V, Mock V, Dow KH, Meares CJ, Grimm PM, Dienemann JA, Haisfield-Wolfe ME, Quitasani F, Mitchell S, Chakravarthy AB, Gage MJ. Exercise is effective in cancer patients with fatigue: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78(11):1199-1207.

[15] Mutrie N, Campbell AM, Whyte F, McConnachie A, Lee L, Kearney N. Benefits of supervised group exercise programme for women being treated for breast cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67(3):343-348.

[16] Craft LL, VanIterson EH, Helenowski IB, Rademaker AW, Courneya KS, King AC, Fitzgibbons JF. Exercise during cancer treatment: effects on chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. J Support Oncol. 2007;5(9):477-484.

[17] Lee J, Shin Y, Straneva PA, Nies MA. Exercise experiences of cancer survivors: a metasynthesis. Cancer Nurs. 2008;31(3):E9-E17.

[18] Stevinson C, Hayes KW, Shane LG, et al. Preoperative exercise and quality of life in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer: a qualitative study. Psychooncology. 2013;22(1):171-177.

[19] Trochim WM. Concept mapping: theory, methodology, application. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1989.

[20] Kane M, Trochim WM. Concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2007.

[21] Rosseel Y. Ariadne 1.3 [computer program]. Wilmslow, England: Minds 21; 2010.

[22] Buffart LM, van Uffelen JG, Riphagen II, et al. Physical and psychosocial benefits of yoga in cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:559.

[23] Leeuwenkamp OR, Buffart LM, den Hollander-van de Beek M, et al. The effect of physical exercise on cancer-related fatigue and physical functioning in patients with cancer during and after treatment: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(1):25-38.

[24] Jackson DN, Kroeker JP. A comparison of concept mapping and multidimensional scaling techniques for the exploration of conceptual structure. Multivar Behav Res. 1988;23(3):345-367.

[25] Kruskal JB, Wish M. Multidimensional scaling. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1978.

[26] Borg I, Groenen PJ. Modern multidimensional scaling: theory and applications. 2nd ed. New York: Springer; 2005.

[27] Schmitz KH, Stout NL, Demark-Wahnefried W, et al. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(7):1409-1426.

[28] Rogers LQ, Macera CA, Ham SA, et al. Psychosocial benefits of a physical activity intervention for breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2008;17(11):1100-1109.

[29] Adamsen L, Quist M, Andersen C, et al. Effect of a multimodal intervention program consisting of exercise, psychosocial support, and dietary advice during chemotherapy on physical function, body composition, quality of life, and side effects in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(7):1058-1067.

[30] Courneya KS, Segal RJ, Mackey JR, et al. Effects of exercise training and psychosocial support on fatigue and quality of life in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(9):1719-1725.

[31] Thorsen L, Thorsen L, Gjerset GM, et al. Impact of exercise on physical and psychological function in women with breast cancer undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;90(1):29-37.

[32] Wolin KY, Schwartz AL, Matthews CE, et al. Implementing the National Cancer Institute’s research recommendations for physical activity and cancer survivorship. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(12):2399-2402.

[33] Vallance JK, Courneya KS, Plotnikoff RC, Yasui Y, Mackey JR. Randomized controlled trial of exercise during adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: quality of life outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(14):1799-1808.

[34] Holmes MD, Chen WY, Feskanich D, Kroenke CH, Colditz GA. Physical activity and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. JAMA. 2005;293(20):2479-2486.

[35] Huber M, Knottnerus JA, Green L, et al. How should we define health? BMJ. 2011;343:d4163.

[36] Rossett A. First things fast: a handbook for performance analysis. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer; 1999.