The Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) has emerged as a vital instrument in the landscape of Cars Assessment Tool For Autism, specifically for diagnosing Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in young children. This article delves into a comprehensive study investigating the effectiveness of CARS in diagnosing ASD in 2-year-old and 4-year-old children referred for potential autism. Our analysis, grounded in rigorous research, aims to provide an enhanced understanding of CARS, offering valuable insights for professionals and caregivers in English-speaking regions seeking reliable autism assessment tools.

Understanding the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS)

The rising prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) underscores the critical need for accurate and early diagnostic tools. ASD, a neurodevelopmental disorder, is characterized by challenges in social interaction, communication deficits, and restricted or repetitive behaviors (American Psychiatric Association 2000). Within the spectrum, conditions like autistic disorder and Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS) represent varying degrees of severity and diagnostic complexities (Volkmar et al. 1994).

PDD-NOS, often considered a less severe form of autism, lacks clear diagnostic boundaries, making its reliable diagnosis challenging (Matson and Boisjoli 2007). It is frequently used when individuals do not fully meet the criteria for autistic disorder or present with atypical autism symptoms (Filipek et al. 1999; Tidmarsh and Volkmar 2003). Given the diagnostic complexities within ASD, especially in young children, tools that offer clear ASD cutoffs are increasingly valuable.

The Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS; Schopler et al. 1980, 1988) is a widely adopted behavior rating scale designed to detect and diagnose autism. It assesses 14 behavioral domains associated with autism, plus a 15th domain for general impressions. Scores range from one to four in each domain, with higher scores indicating greater impairment. Total scores, ranging from 15 to 60, help categorize individuals into non-autistic, mild to moderate autism, or severe autism ranges (Schopler et al. 1988). The CARS has demonstrated robust psychometric properties, making it a reliable tool in autism diagnosis (Schopler et al. 1988; Perry and Freeman 1996; Nordin et al. 1998; Tachimori et al. 2003).

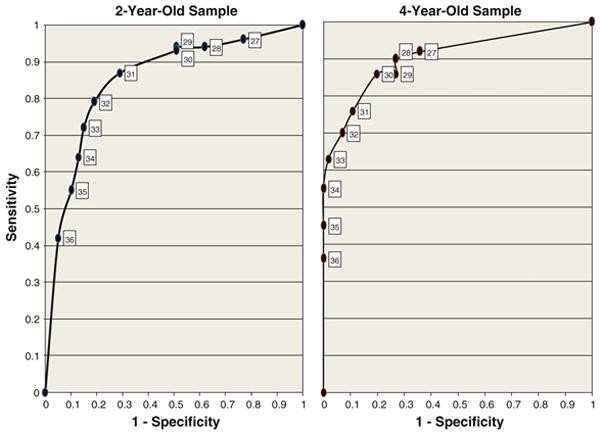

Fig 1: ROC curves illustrating the effectiveness of different CARS cutoffs for diagnosing autistic disorder in 2-year-old and 4-year-old samples, showcasing the tool’s diagnostic capability as a cars assessment tool for autism.

CARS and DSM-IV Agreement: Validating Diagnostic Accuracy

Studies have consistently shown strong agreement between CARS classifications and DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for autistic disorder. For instance, Perry et al. (2005) found an 88% agreement rate in a sample of preschool children (Perry et al. 2005). Rellini et al. (2004) reported complete agreement in a study of children aged 18 months to 11 years (Rellini et al. 2004). Ventola et al. (2006) also reported high chance-corrected agreement (κ = 0.691) (Ventola et al. 2006), and Eaves and Milner (1993) noted a high sensitivity of 0.98 when using CARS for diagnosing autistic disorder (Eaves and Milner 1993).

However, research also indicates that CARS might over-diagnose autism in very young children. Lord (1995) found that CARS tended to classify non-autistic intellectually disabled 2-year-olds as autistic (Lord 1995). Lord’s study suggested that increasing the CARS cutoff score from 30 to 32 improved diagnostic accuracy for 2-year-olds by reducing false positives without sacrificing the identification of true positives.

A significant limitation of the original CARS is the absence of an empirically validated ASD cutoff. While group differences in CARS total scores have been observed across clinical groups (Perry et al. 2005), CARS was not initially designed to differentiate PDD-NOS from autistic disorder or ASD from non-spectrum conditions. This lack of a clear ASD cutoff can lead to reduced diagnostic agreement with other autism diagnostic instruments and clinical judgment (Chlebowski et al. 2008).

Optimizing CARS Cutoffs for Accurate ASD Diagnosis

Determining optimal cutoff scores for ASD on CARS requires balancing sensitivity (correctly identifying ASD cases) and specificity (correctly identifying non-ASD cases). For diagnostic purposes, moderate sensitivity and good specificity are crucial to minimize both false positives and false negatives, ensuring accurate diagnoses and appropriate interventions (Filipek et al. 1999).

Tachimori et al. (2003) investigated a PDD cutoff using the Tokyo version of CARS (CARS-TV) in a Japanese sample. They found that a cutoff score of 25.5/26 effectively distinguished PDD from mental retardation without PDD, with good sensitivity and specificity (Tachimori et al. 2003). This finding highlights the potential of refining CARS cutoffs to enhance its diagnostic utility as a cars assessment tool for autism.

Current Study: Investigating CARS in Young Children

Our study aimed to evaluate CARS in a clinical sample of young children with suspected ASD. The objectives were threefold:

- Replicate previous studies to determine the ideal CARS cutoff for autistic disorder diagnosis in toddlers and preschool children.

- Calculate sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values to identify the optimal CARS cutoff for an ASD diagnosis, expanding its application as a cars assessment tool for autism.

- Assess the impact of a CARS ASD cutoff on diagnostic agreement between CARS, ADOS (Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule), and clinical judgment based on DSM-IV criteria.

Methodology

Participants

The study included 606 children (482 males, 124 females) who had failed the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT; Robins et al. 2001) and follow-up interview. Participants were divided into two age groups: a 2-year-old sample (n = 376, ages 21-30 months) and a 4-year-old sample (n = 230, ages 42-66 months). A subset of 173 children participated in evaluations at both ages.

Children were categorized into four diagnostic groups based on clinical best estimate using DSM-IV criteria, ADOS, Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R), parent interviews, and direct observation:

- Autistic Disorder Group: Met DSM-IV criteria for autistic disorder.

- PDD-NOS Group: Diagnosed with PDD-NOS.

- Non-ASD Diagnosis Group: Diagnosed with intellectual disability, global developmental delay, or other non-ASD conditions.

- No Diagnosis Group: Did not meet criteria for any DSM-IV diagnosis, including typically developing children (see Table 1).

Table 1. Sample Characteristics

| Diagnostic group | Sample characteristics | 2-year-old sample | 4-year-old sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 376 | n = 230 | ||

| Autistic disorder | Sample size | n = 142 | n = 104 |

| Mean age (SD) | 26.8 (4.7) | 53 (10.3) | |

| Gender | 78% male | 86% male | |

| Mean CARS score (SD) | 35.1 (4.2) | 34.2 (5) | |

| MSEL ELC (SD)a | 58.7 (10.9) | 59.4 (16.1) | |

| Mean ADOS cutoff score (SD)b | 16.57 (4.12) | 15.46 (4.34) | |

| PDD-NOS | Sample size | n = 101 | n = 44 |

| Mean age (SD) | 25.9 (4.4) | 52.7 (9.1) | |

| Gender | 78% male | 75% male | |

| Mean CARS score (SD) | 29 (4) | 25.9 (3.4) | |

| MSEL ELC (SD)a | 63.2 (11) | 84.8 (18.2) | |

| Mean ADOS cutoff score (SD)b | 12.97 (4.66) | 9.71 (3.42) | |

| Non-ASD diagnosis | Sample size | n = 95 | n = 34 |

| Mean age (SD) | 26.6 (4.5) | 53.4 (6.6) | |

| Gender | 84% male | 88% male | |

| Mean CARS score (SD) | 22.5 (3.2) | 21.7 (3) | |

| MSEL ELC (SD)a | 68.4 (14.7) | 74.1 (19.5) | |

| Mean ADOS cutoff score (SD)b | 4.57 (3.79) | 3.36 (2.33) | |

| No diagnosis | Sample size | n = 38 | n = 48 |

| Mean age (SD) | 23.4 (4.1) | 58.1 (17.9) | |

| Gender | 71% male | 65% male | |

| Mean CARS score (SD) | 19.7 (3.4) | 17.8 (2.2) | |

| MSEL ELC (SD)a | 95.6 (12.9) | 98.9 (12.4) | |

| Mean ADOS cutoff score (SD)b | 4.11 (3.75) | 1.78 (2.11) |

aMSEL ELC results from a sub-set of children who received the mullen scales of early learning. (2-year-old sample: autistic disorder n = 120; PDD-NOS n = 94; Non ASD n = 84; no diagnosis n = 35); (4-year-old sample: autistic disorder n = 82; PDD-NOS n = 35; Non ASD n = 28; No diagnosis n = 37)

bADOS results from a sub-set of children who received the autism diagnostic observation schedule. (2-year-old sample: autistic disorder n = 130; PDD-NOS n = 97; Non ASD n = 91; No diagnosis n = 36); (4-year-old sample: autistic disorder n = 91; PDD-NOS n = 38; Non ASD n = 25; No diagnosis n = 36)

Procedure

Data were collected during initial and follow-up developmental evaluations at the University of Connecticut. Evaluations, conducted by licensed psychologists or developmental pediatricians and doctoral students, included CARS, ADOS, ADI-R, Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL), and clinical diagnoses based on DSM-IV-TR criteria.

Instruments

- Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT): Parent-report screening tool for ASD in children aged 16–30 months (Robins et al. 2001).

- Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS): Behavioral rating scale assessing ASD symptoms, completed by evaluators using clinical observations, test results, and parent reports (Schopler et al. 1980, 1988). Inter-rater reliability was high (r = 0.94, kappa = 0.90).

- Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS): Semi-structured, standardized assessment of communication, social interaction, and play (Lord et al. 2000).

- Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL): Cognitive development measure for children up to 68 months (Mullen 1995).

- Clinical Judgment: DSM-IV-TR criteria-based diagnoses by experienced clinicians, considered the gold standard for autism diagnosis (Spitzer and Siegel 1990; Klin et al. 2000).

Results

Sample Characteristics and Internal Consistency

No significant age or ethnicity differences were found across diagnostic groups within each age sample. Developmental quotient (DQ) scores from MSEL showed significant differences across diagnostic groups, with the ‘No Diagnosis’ group having the highest DQ scores. CARS demonstrated excellent internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91 for the entire sample.

CARS Scores and Diagnostic Groups

Mean CARS scores significantly differed across diagnostic groups in both age samples. Children with autistic disorder had the highest mean CARS scores, followed by PDD-NOS, Non-ASD, and No Diagnosis groups, reflecting varying autism severity levels.

CARS Cutoff for Autistic Disorder

For 2-year-olds, a CARS cutoff of 32 optimized the balance between sensitivity (0.79) and specificity (0.81) in distinguishing autistic disorder from PDD-NOS. For 4-year-olds, a cutoff of 30 showed good sensitivity (0.86) and specificity (0.80).

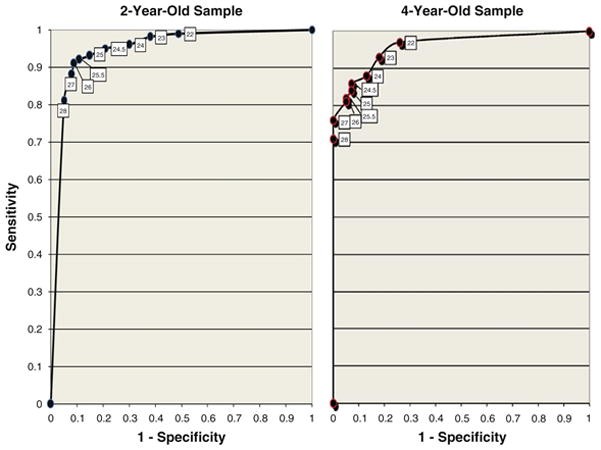

CARS Cutoff for ASD Diagnosis

A CARS cutoff of 25.5 demonstrated excellent sensitivity (0.92) and good specificity (0.89) for diagnosing ASD in 2-year-olds. In 4-year-olds, a cutoff of 25.5 also showed adequate sensitivity (0.82) and high specificity (0.95) for ASD diagnosis, suggesting its validity across age groups as a cars assessment tool for autism.

Fig 2: ROC curves highlighting the effectiveness of different CARS cutoffs in diagnosing ASD across 2-year-old and 4-year-old samples, demonstrating its utility as a reliable cars assessment tool for autism diagnosis.

Impact of CARS Cutoff on Diagnostic Agreement

Using a CARS ASD cutoff of 25.5 significantly improved diagnostic agreement between CARS, DSM-IV clinical judgment, and ADOS in both age samples compared to using the traditional cutoff of 30. Agreement levels increased to “excellent” for CARS and DSM-IV criteria and “good” for CARS and ADOS with the 25.5 cutoff, enhancing the reliability of CARS as a cars assessment tool for autism.

Table 6. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive values and negative predictive values of CARS cutoffs for diagnosis of ASD in a 2-year-old sample (N = 376)

| CARS cut-off | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive predictive value | Negative predictive value | False positive errorsa | False negative errorsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | 0.99 | 0.42 | 0.76 | 0.98 | 77 | 1 |

| 21.5 | 0.99 | 0.48 | 0.78 | 0.97 | 69 | 2 |

| 22 | 0.99 | 0.51 | 0.79 | 0.97 | 65 | 2 |

| 22.5 | 0.98 | 0.57 | 0.80 | 0.94 | 57 | 5 |

| 23 | 0.98 | 0.62 | 0.83 | 0.93 | 50 | 6 |

| 23.5 | 0.97 | 0.66 | 0.84 | 0.93 | 45 | 7 |

| 24 | 0.96 | 0.70 | 0.85 | 0.90 | 40 | 10 |

| 24.5 | 0.95 | 0.79 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 28 | 13 |

| 25 | 0.93 | 0.85 | 0.92 | 0.87 | 20 | 17 |

| 25.5 | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.94 | 0.85 | 14 | 19 |

| 26 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.95 | 0.85 | 12 | 21 |

| 26.5 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.95 | 0.84 | 12 | 24 |

| 27 | 0.88 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.81 | 11 | 28 |

| 27.5 | 0.85 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.78 | 8 | 36 |

| 28 | 0.81 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.73 | 6 | 46 |

| 28.5 | 0.79 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.71 | 6 | 52 |

| 29 | 0.77 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.69 | 6 | 57 |

| 29.5 | 0.75 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.68 | 6 | 61 |

aFalse positive and false negative errors are reported for each CARS cutoff using diagnosis based on clinical judgment as the gold standard for diagnosis

Discussion and Conclusion

This study reinforces the CARS as a reliable and valid cars assessment tool for autism in young children. The findings support adjusting the CARS cutoff for autistic disorder to 32 for 2-year-olds and maintaining the cutoff at 30 for 4-year-olds. Crucially, the study provides empirical evidence for an ASD cutoff of 25.5 on CARS, enhancing diagnostic accuracy and agreement with other established diagnostic methods.

The use of an ASD cutoff of 25.5 on CARS improves its utility in clinical settings, particularly for early ASD diagnosis in toddlers and preschool children. This refined cutoff enhances diagnostic agreement with ADOS and clinical judgment, streamlining the diagnostic process and improving the accuracy of ASD diagnoses.

Limitations

Study limitations include a clinically referred sample, predominantly Caucasian and male, limiting generalizability. The inclusion of children slightly younger than the validated age range for CARS (under 24 months) may also influence results, although subgroup analyses showed consistency. The inherent dependency of CARS scores on clinical judgment is another limitation, as clinical diagnoses were not entirely independent of CARS assessments in this study. Finally, the study emphasizes that CARS effectiveness is contingent on the quality of behavioral observation and clinician expertise.

Despite these limitations, this research strongly advocates for the use of a CARS ASD cutoff of 25.5 to improve diagnostic accuracy and agreement in young children referred for ASD, reinforcing its role as a valuable cars assessment tool for autism in early intervention and diagnostic practices.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to all participating children and families, pediatricians, early intervention providers, and the Early Detection Advisory Board. Special thanks to Jillian Wood, Dr. Ho-Wen Hsu, Dr. Mark Greenstein, clinicians, graduate students, and undergraduate research assistants for their invaluable contributions. This study was supported by NIH and Maternal and Child Health Bureau grants, and prior funding from the National Association for Autism Research, NIMH, and the Department of Education. This paper is based on the master’s thesis of Colby Chlebowski at the University of Connecticut.