I. Introduction

The intensive care unit (ICU) is designed to provide life-saving interventions for critically ill patients. However, for some, these advanced technologies can prolong suffering when recovery is unlikely. Many individuals nearing the end of life (EoL) would prefer less aggressive, comfort-focused care, yet these preferences are often not documented in medical records. This gap necessitates goals-of-care discussions in the ICU, involving clinicians and substitute decision-makers (SDMs), often under stressful circumstances. To aid these complex conversations, various communication tools have been developed. This article delves into the effectiveness of these cares tools for end of life in the ICU setting.

II. The Need for Structured Communication in End-of-Life Care

A. The Challenge of End-of-Life Decisions in the ICU

ICUs are high-stakes environments where rapid, critical decisions are made. When patients are unable to express their wishes, SDMs and healthcare professionals must navigate intricate ethical and medical dilemmas to determine the most appropriate course of action. These decisions frequently involve considering limitations of treatment, including whether to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining interventions. The emotional weight of these decisions, coupled with the time-sensitive nature of ICU care, underscores the need for effective cares tools for end of life.

B. What are Cares Tools for End of Life?

Cares tools for end of life encompass a range of structured interventions designed to improve communication and decision-making around EoL care. These tools are not simply about sharing information; they actively assist patients (when possible) and SDMs in understanding their options, clarifying values, and making informed choices. These tools can include:

- Decision Aids: Materials (paper, video, or digital) that explain treatment options, probabilities, and potential outcomes.

- Structured Meeting Plans: Frameworks for organizing and conducting goals-of-care conversations, ensuring key topics are addressed.

- Educational Interventions: Programs to enhance communication skills for healthcare providers and improve understanding of EoL care for families.

- Ethics or Palliative Care Consultations: Specialized services to facilitate complex EoL discussions and provide expert guidance.

C. The Gap in Evidence: Are Cares Tools Effective?

Despite the development and implementation of various cares tools for end of life, uncertainty persists regarding their impact. Are these tools truly superior to standard, ad hoc approaches to EoL decision-making in the ICU? To address this question, a systematic review was conducted to analyze the existing medical literature.

III. Methodology: A Systematic Review of Communication Tools in the ICU

A. Review Protocol and Registration

A rigorous systematic review protocol was established and registered with PROSPERO (CRD42014012913) to ensure transparency and methodological rigor.

B. Eligibility Criteria for Studies

The review included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and prospective observational studies with control groups that evaluated cares tools for end of life in adult ICU patients. Studies were required to be published in peer-reviewed English language journals. The focus was on tools specifically designed to assist EoL decision-making, excluding interventions solely aimed at information sharing or emotional support. Studies conducted in ambulatory or non-ICU inpatient settings were excluded to maintain focus on the unique challenges of the ICU environment.

Table 1. Study Eligibility Criteria

| Eligibility criterion | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Randomized, controlled trial or prospective observational study, published in peer-reviewed journal | Randomized controlled trials and prospective observational study experimental designs are least likely to lead to biased results |

| Evaluates a structured communication tool (decision aid, structured meeting, educational strategy) compared to control group | • Interest in comparing wide variety of interventions, in multiple formats (verbal, paper, video, computer, etc.)• A control group is required to assess whether the intervention is better than usual care as routinely practiced (recognizing that usual care may vary based on setting) |

| Communication tool must address end-of-life decision-making | Review interest is in interventions that assist patients with decision-making, as opposed to those that address breaking bad news, patient comfort alone |

| Adult patients (age >18 years) | End-of-life decision-making process in frail adults is likely to be qualitatively different from that in children |

| English language | Communication tools published in other languages, with no English translation available, may not be generalizable to english-language settings |

Study eligibility criteria for the systematic review.

C. Information Sources and Search Strategy

A comprehensive search was conducted across major databases including MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, ERIC, and Cochrane, spanning from database inception to July 2014. Search terms focused on “communication,” “decision-making,” “end-of-life,” and “cardiopulmonary resuscitation.” Reference lists of eligible articles were also hand-searched to identify additional relevant studies.

D. Study Selection and Data Collection

Two independent reviewers screened titles and abstracts, followed by full-text reviews for potentially eligible articles. Disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer. Data extraction was performed using standardized forms, and study authors were contacted for missing data.

E. Risk of Bias Assessment

The risk of bias within individual studies was assessed using established tools: the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for RCTs and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for observational studies. This rigorous assessment ensured the quality of included evidence was carefully considered.

F. Data Synthesis and Analysis

Meta-analysis was performed using Revman 5.3 software. Pooled estimates of effect were calculated using random-effects models. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I² statistic. The GRADE approach was used to evaluate the overall quality of evidence for each outcome.

IV. Results: Impact of Cares Tools on End-of-Life Outcomes in the ICU

A. Study Selection and Characteristics

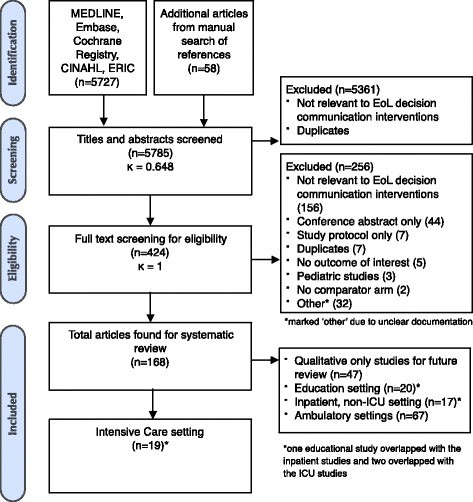

The initial search yielded 5785 abstracts, with 168 articles meeting eligibility criteria, including 19 studies conducted specifically in the ICU. The studies varied in intervention types, target populations, and outcome measures, reflecting the diverse landscape of cares tools for end of life.

Fig. 1. Flowsheet of study screening, eligibility, and inclusion

Flow diagram illustrating the study selection process for the systematic review.

B. Primary Outcomes: Documentation of Goals of Care, Code Status, and Treatment Decisions

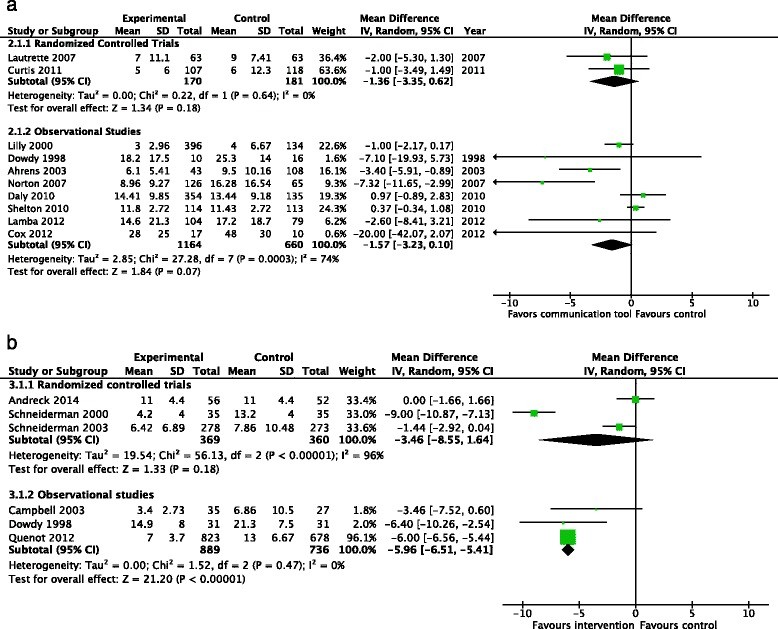

- Documented Goals-of-Care Discussions: The use of cares tools for end of life was associated with a significant increase in the documentation of goals-of-care discussions (RR 3.47, 95% CI 1.55, 7.75, p = 0.020). However, the quality of evidence was rated as very low.

Fig. 2. Proportion of patients with documented goals-of-care discussions

Forest plot depicting the effect of communication tools on documented goals-of-care discussions.

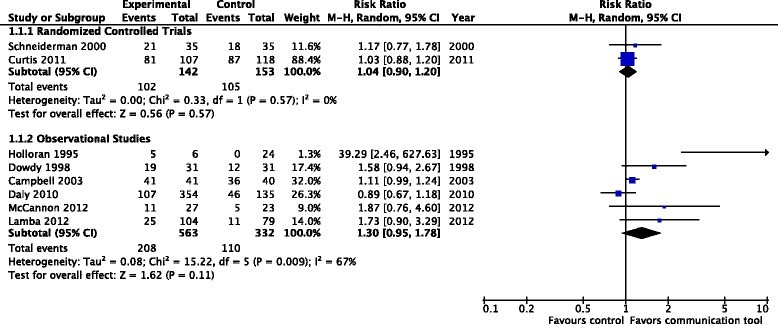

- Documented Code Status: Cares tools for end of life did not demonstrate a statistically significant effect on the documentation of code status (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.96, 1.10, p = 0.540). The quality of evidence was low.

Fig. 3. Documented code status/’do not resuscitate’ status

Forest plot illustrating the effect of communication tools on documented code status.

- Decisions to Withdraw or Withhold Life-Sustaining Treatments: Similarly, cares tools for end of life did not significantly impact decisions to withdraw or withhold life-sustaining treatments (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.89, 1.08, p = 0.70). The quality of evidence was low.

Fig. 4. Documented decisions to withdraw or withhold treatments

Forest plot showing the effect of communication tools on decisions to withdraw or withhold treatments.

C. Secondary Outcomes: Resource Utilization and Other Measures

Interestingly, cares tools for end of life were associated with a reduction in several measures of healthcare resource utilization:

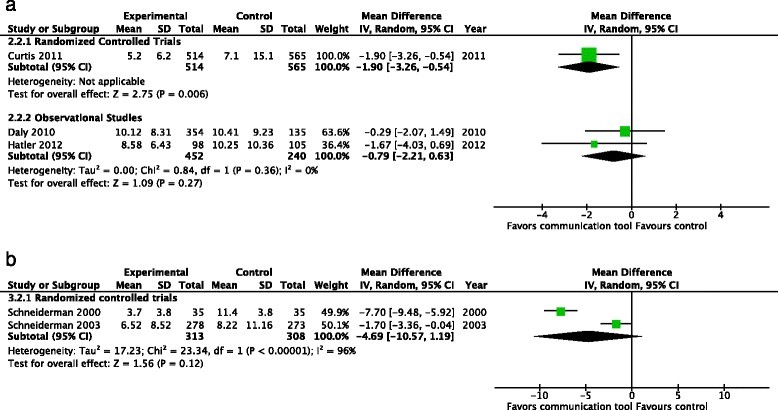

- Duration of Mechanical Ventilation: Mean difference (MD) -1.9 days (95% CI -3.26, -0.54, p = 0.006).

- Length of ICU Stay: MD -1.11 days (95% CI -2.18, -0.03, p = 0.04).

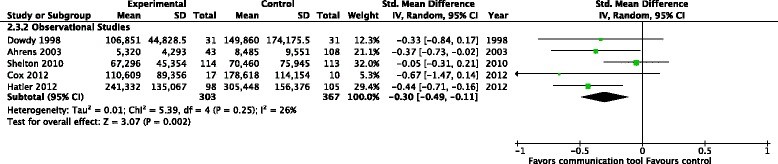

- Healthcare Costs: Standardized mean difference (SMD) -0.32 (95% CI -0.5, -0.15, p < 0.001).

However, the quality of evidence for these outcomes was also very low. There was no significant effect observed in the subgroup analysis of ICU non-survivors.

Fig. 7. Health care resource utilization – duration of mechanical ventilation (days)

Forest plot demonstrating the effect of communication tools on duration of mechanical ventilation.

Fig. 8. Health care resource utilization – length of intensive care unit stay (days)

Forest plot illustrating the effect of communication tools on length of ICU stay.

Fig. 10. Health care resource utilization – financial costs

Forest plot showing the effect of communication tools on healthcare costs.

V. Discussion: Interpreting the Evidence and Future Directions

A. Limited Evidence for Improved End-of-Life Documentation

The review revealed surprisingly limited high-quality evidence supporting the effectiveness of cares tools for end of life in improving documentation of crucial EoL decisions like code status and treatment withdrawal. While documentation of goals-of-care discussions increased, the very low quality of evidence necessitates cautious interpretation. The lack of strong evidence may be due to various factors, including study limitations, the inherent complexity of measuring EoL decision-making, or the possibility that current standard care already addresses some aspects effectively.

B. Potential for Reduced Resource Utilization

The finding that cares tools for end of life may reduce healthcare resource utilization, despite the low quality of evidence, is noteworthy. This suggests that these tools might influence the intensity of care provided, potentially aligning it better with patient wishes and reducing interventions that are not beneficial. However, the mechanisms behind this reduction remain unclear and require further investigation. It’s possible that improved communication leads to less aggressive care pathways, even if formal documentation of DNR orders or treatment withdrawal is not significantly altered.

C. The Need for High-Quality Research

The low to very low quality of evidence across most outcomes underscores the urgent need for more robust, high-quality randomized controlled trials. Future research should focus on:

- Targeted Populations: Investigating the effectiveness of cares tools for end of life in specific ICU patient subgroups, such as those with goals-of-care conflicts or prolonged ICU stays.

- Comprehensive Outcome Measures: Including patient-centered outcomes like concordance between patient wishes and received care, family satisfaction, and long-term psychological impact on families, alongside system-level outcomes like resource utilization.

- Earlier Intervention: Exploring the potential benefits of implementing structured communication tools earlier in the patient’s care trajectory, before ICU admission, to facilitate advance care planning and prevent crises.

D. Strengths and Limitations of the Review

This systematic review’s strengths lie in its broad search strategy, rigorous methodology, and use of GRADE to assess evidence quality. However, limitations include the heterogeneity of included studies, the challenges in identifying studies specifically focused on EoL decision-making tools, and the reliance on surrogate outcome measures like documentation rates.

VI. Conclusion: Moving Forward in End-of-Life Care in the ICU

This systematic review provides a comprehensive analysis of the evidence for cares tools for end of life in the ICU. While the use of these tools may improve documentation of goals-of-care discussions and potentially reduce healthcare resource utilization, the supporting evidence is currently of low to very low quality. More rigorous research, particularly high-quality RCTs, is crucial to determine the true impact of structured communication interventions on patient, family, and system-level outcomes in ICU end-of-life care. Future efforts may also benefit from exploring the implementation of these tools earlier in the course of illness, before critical care becomes necessary.

VII. Key Messages

- Numerous studies have examined structured communication tools to enhance end-of-life decision-making in adult ICU patients.

- Current evidence for the effectiveness of these interventions in increasing documentation of goals of care, code status, or treatment withdrawal is of low to very low quality.

- Future research should focus on simple interventions in targeted ICU populations, reporting patient-level, family-level, and system-level outcomes to provide a more complete picture of their impact.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the Technology Evaluation in the Elderly Network (TVN Grant #KS 2014 – 06). TVN had no role in the design, conduct, or publication of the study.

Abbreviations

CI: confidence interval

DNR: do not resuscitate

EoL: end of life

GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation

HCP: health care provider

ICU: intensive care unit

MD: mean difference

RCT: randomized controlled trial

RR: relative risk

SDM: substitute decision-makers

SMD: standardized mean difference

Additional file

Additional file 1: Appendix: Electronic search strategies. (DOC 72 kb)

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SO and HC conceived and designed the project, conducted the research, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. LH designed the project, interpreted the data, and edited the manuscript. LM interpreted the data and edited the manuscript. JY designed the project, conducted the research, interpreted the data and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Simon J. W. Oczkowski, Email: oczkowsj@mcmaster.ca

Han-Oh Chung, Email: hanoh.chung@mcmaster.ca.

Louise Hanvey, Email: lhanvey@rogers.com.

Lawrence Mbuagbaw, Email: mbuagblc@mcmaster.ca.

John J. You, Email: jyou@mcmaster.ca