Ensuring the quality of care provided to patients is paramount in daily clinical practice and healthcare policy. Various tools exist to evaluate and enhance care, including incident analysis, health technology assessment, and clinical audits. Clinical audits involve comparing clinical outcomes or processes against established standards based on evidence-based medicine to pinpoint areas needing improvement. This article explores the principles of clinical audits, focusing on their application in care services.

Defining Clinical Audits and Their Purpose

A clinical audit is a systematic process that measures healthcare practices against pre-defined standards. Its primary goal is to identify discrepancies between actual practice and the established standards, leading to improvements in the quality of care. Unlike clinical research, which seeks to discover new best practices, clinical audits evaluate existing practices against known standards. The ultimate aim is to enhance patient care by:

- Expanding clinician knowledge: Audits can highlight areas where clinicians need further training or education.

- Problem-solving: Identifying and addressing specific issues within a care setting.

- Standardizing practices: Reducing variations in professional conduct to ensure consistency in care delivery.

- Bridging the gap: Aligning theoretical standards with real-world practice.

Key Steps in Conducting a Clinical Audit

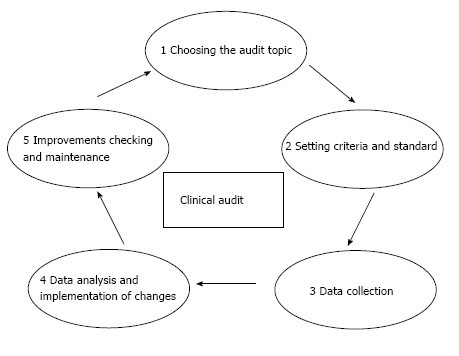

A successful clinical audit involves a cyclical process with five key steps:

1. Preparation: Laying the Groundwork

Careful planning is essential. This includes:

- Topic Selection: Choosing a relevant area with significant clinical importance, measurable outcomes, and potential for impactful improvements. High-volume, high-cost, high-risk, highly variable, complex, or innovative areas are good candidates.

- Defining Objectives: Clearly outlining the audit’s purpose, whether it’s implementing new protocols or enhancing existing ones.

- Resource Allocation: Securing necessary staff, funding, and tools for data collection and analysis.

2. Establishing Criteria and Standards

- Indicators: Defining measurable variables to track changes related to the chosen criteria.

- Criteria: Specifying aspects of healthcare that reflect its quality, based on evidence-based practices.

- Standards: Setting the desired level of performance for each criterion, often expressed as a percentage. Standards should be derived from reputable sources like guidelines and scientific literature.

3. Data Collection: Gathering Evidence

Data can be collected prospectively (real-time) or retrospectively (from existing records). Prospective audits offer greater accuracy but require more time and resources. Methods include:

- Quantitative data: Numerical data from medical records, lab results, etc.

- Qualitative data: Information from interviews, questionnaires, and observations.

Patient confidentiality must be maintained throughout the data collection process.

4. Analysis and Corrective Actions: Identifying and Addressing Gaps

Comparing collected data with established standards reveals areas where improvements are needed. If standards aren’t met, the audit team should:

- Analyze barriers: Identify factors hindering the achievement of standards.

- Develop interventions: Formulate clear, feasible recommendations for improvement, considering organizational context and resources.

- Communicate findings: Share results and recommendations with all stakeholders.

5. Verification and Sustainability: Ensuring Long-Term Improvement

The final step involves:

- Monitoring: Regularly checking the impact of implemented changes.

- Adjusting strategies: Modifying interventions if initial efforts are insufficient.

- Maintaining improvements: Ensuring long-term adherence to improved practices.

Clinical Audits in Nephrology: Real-World Applications

Clinical audits have been extensively used in nephrology to address various challenges, including:

- Vascular Access Management: Optimizing dialysis access choices.

- Hypertension Control: Improving blood pressure management in dialysis patients.

- Mineral Metabolism Management: Addressing mineral bone disorders in chronic kidney disease.

Figure 1

Figure 1

Clinical audit cycle.

Conclusion: The Value of Auditing Tools

Clinical audits are invaluable tools for enhancing the quality of care services. They provide a structured framework for identifying areas needing improvement and implementing effective changes. By embracing a continuous cycle of evaluation and refinement, healthcare providers can ensure the delivery of optimal care to their patients. While evidence supporting the effectiveness of clinical audits is mixed, their potential to drive positive change in healthcare settings remains significant. Further research is needed to validate their efficacy in diverse contexts. A systematic approach to planning, implementing, and monitoring clinical audits is crucial for maximizing their impact.