Introduction

In resource-rich countries like the United States, maternal and newborn health outcomes lag significantly behind global standards, with a concerning number of pregnancy-related deaths being preventable. This stark reality underscores the urgent need for improved and accessible maternity care. Severe maternal morbidity and mortality have far-reaching consequences, impacting individuals and families, and highlighting systemic gaps in healthcare. Many pregnant individuals lack consistent access to comprehensive, evidence-based maternity care, while healthcare providers often grapple with insufficient data and limited guidelines to inform critical clinical decisions. This is partly due to the exclusion of pregnant and lactating individuals from many clinical trials and the limitations of studies with small sample sizes.

To bridge this critical gap, Clinical Decision Support Systems (CDSS) are increasingly recognized for their potential in pregnancy care. Leading organizations like the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists advocate for CDSS to enhance patient management within clinical information systems, including Electronic Health Records (EHRs). Pregnancy care is uniquely complex, characterized by diverse data types – clinical findings, medical imaging, genetic testing, and multi-specialty involvement spanning obstetrics, gynecology, and neonatology, across the entire pregnancy journey from preconception to postpartum. Effective clinical decision support in this intricate landscape demands seamless EHR interoperability and robust clinical validity. Within this context, pregnancy care encompasses healthcare for both mothers and their babies throughout the pre-pregnancy, pregnancy, and postpartum phases. Beyond improving direct patient care, CDSS is vital for promoting evidence-based medicine, creating a learning health system where readily available digital data is translated into actionable knowledge for improved treatments and patient outcomes.

The rapid advancement of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and biomedical informatics is transforming clinical medicine. In healthcare, AI broadly refers to computer systems designed to perform tasks typically requiring human cognitive abilities. AI’s integration into CDSS is becoming increasingly crucial, enhancing knowledge discovery, diagnostic precision, risk prediction, chronic disease management, and patient monitoring. Specifically in pregnancy care, emerging research explores the transformative potential of AI-augmented CDSS to optimize clinical workflows and patient management. However, the vast array of clinical guidelines, diverse AI techniques, and varying EHR systems create a complex landscape, making the precise capabilities and characteristics of AI-augmented CDSS in pregnancy care still unclear. While AI applications in obstetrics and gynecology are growing, comprehensive reviews focusing on AI-augmented CDSS specifically tailored for pregnancy care are notably absent.

A systematic review is essential to address critical gaps in current understanding. Firstly, maternal health decisions are highly sensitive and often based on limited evidence-based guidelines. This necessitates CDSS designs that incorporate both established clinical guidelines, carefully selected clinical data, and crucially, shared patient preferences and consent. These design considerations likely vary across different stages and specialties within pregnancy care, requiring systematic investigation that current reviews haven’t provided. Secondly, AI applications in CDSS for pregnancy care have evolved significantly in recent years. While the definition of AI remains broad, a systematic review is needed to update the current state-of-the-art AI methodologies applied to pregnancy-related CDSS and to compare them against earlier AI technologies. Thirdly, existing reviews often focus solely on evaluating AI methods and model performance in isolation (e.g., prediction accuracy). Crucially missing is an evaluation that combines model performance with the assessment of CDSS implementation outcomes in real-world clinical settings. This perspective is vital for understanding the external validity and practical impact of CDSS research.

Therefore, this study aims to provide a systematic review of empirical studies examining automated risk assessment tools for pregnancy care through AI-augmented CDSS. We intend to illuminate the challenges and opportunities these tools present for improving pregnancy care, using the established framework of participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study design. Specifically, we aim to: (1) pinpoint the specific domains within maternal care where AI-augmented CDSS plays a significant role, (2) characterize the current functionalities of these CDSS tools, and (3) identify the limitations, challenges, and future opportunities in this rapidly evolving field.

Methods

This literature review adhered to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines. The PRISMA checklist is available in Multimedia Appendix 1.

Bibliographic Database

We conducted searches across three prominent electronic bibliographic databases: PubMed/MEDLINE (encompassing MEDLINE and PubMed Central [PMC]), Embase, and ACM Digital Library. PubMed/MEDLINE is a leading database for life sciences and biomedical literature, managed by the US National Library of Medicine. PMC serves as a digital archive for full-text biomedical and life sciences journal articles. Embase is a comprehensive database with a strong focus on pharmacovigilance. The ACM Digital Library is a key resource for computing and information technology literature, including biomedical informatics and digital health. Access to Embase and ACM Digital Library was provided by the University of South Carolina.

Search Strategy

In PubMed/MEDLINE, we used search strings within the “text word” field, which includes titles, abstracts, keywords, MeSH terms, publication types, and other relevant terms. To capture topics potentially missed by “text word,” we also searched within [MeSH Major Topic]. We adapted the PubMed/MEDLINE search strategy for Embase and ACM Digital Library, considering that MeSH terms are unique to PubMed/MEDLINE and other field variations across databases. For all databases, the publication timeframe was limited to 2022 and earlier, with no language restrictions. Search strings incorporated terms related to pregnancy procedures, pregnancy outcomes, CDSS models, CDSS methods, and AI methodologies (see Multimedia Appendix 2 for detailed search strings and criteria). All database searches were completed in January 2023. The search strategy was developed collaboratively by authors CL and TL, incorporating suggestions from other authors, and the searches were performed by NG.

Assessment of Eligibility and Biases

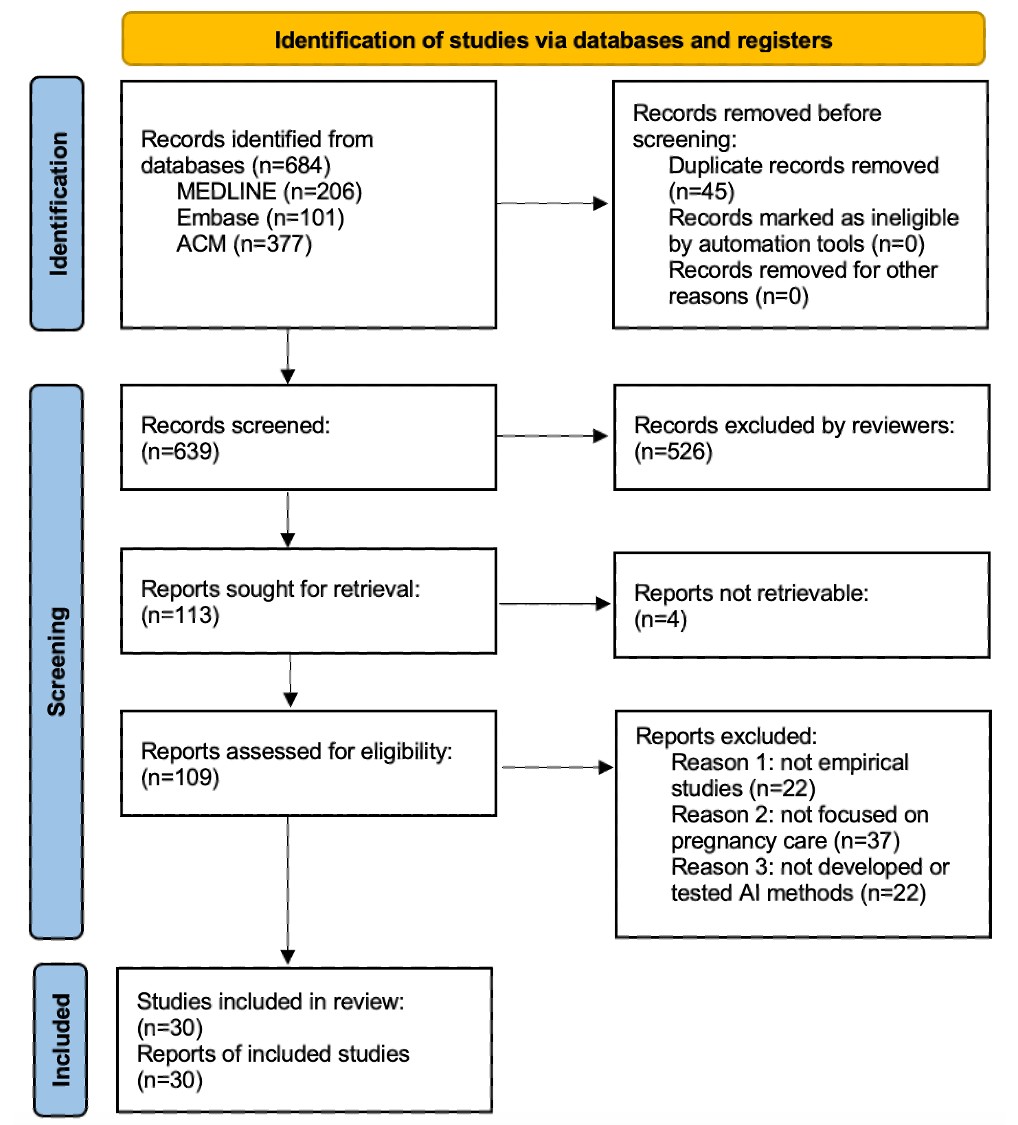

Author NG removed duplicate entries by comparing PubMed Identifiers, titles, publications, and authors across databases. Eligibility assessment followed these inclusion criteria: empirical studies that (1) developed or tested AI methods, (2) developed or tested CDSS or CDSS components, and (3) focused on pregnancy care. Study quality and bias were evaluated using criteria adapted from the Risk of Bias 2 tool, including: (1) empirical study design, (2) primary focus on “pregnancy care,” “CDSS,” and “AI,” and (3) completeness, clarity, and validity of reported methods, results, and conclusions. Full-text manuscripts of potentially relevant studies were reviewed for final inclusion. Two reviewers (TL and NG) independently assessed publications for inclusion and quality, resolving discrepancies through discussion with a senior reviewer (CL) for final decisions. This process resulted in 30 studies selected for review (see Figure 1 for the study selection process).

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart. AI: artificial intelligence; PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses. Note: Under “Reports excluded,” exclusion reasons #1, #2, and #3 are not mutually exclusive.

Data Synthesis

When studies reported ancillary information (e.g., pilot studies) or overlapping outcomes across multiple publications, they were treated as a single study unit. Two independent coders (CL and TL) extracted study information including: authors and year, study objectives, pregnancy care applications, CDSS functionality, data source, study population, AI methods, CDSS performance, validation, and implementation. Pregnancy care applications were categorized into prenatal and early pregnancy care, obstetric care, and postpartum care. Obstetric complications in this review include maternal (e.g., perinatal hemorrhage, ectopic pregnancy, eclampsia, gestational diabetes), fetal (e.g., miscarriage, stillbirth, preterm birth), and neonatal (e.g., bradycardia, tachyarrhythmia) adverse events. These categories are not mutually exclusive. CDSS functionality related to “clinical prediction” refers to predicting adverse clinical events, outcomes, prognosis, and identifying individuals at risk. Validation types were defined as internal validation (model performance within the study context, using data partitioned from a homogenous dataset) and external validation (model performance outside the study context, emphasizing generalizability across different settings).

Results

Study Selection and Synthesis of Results

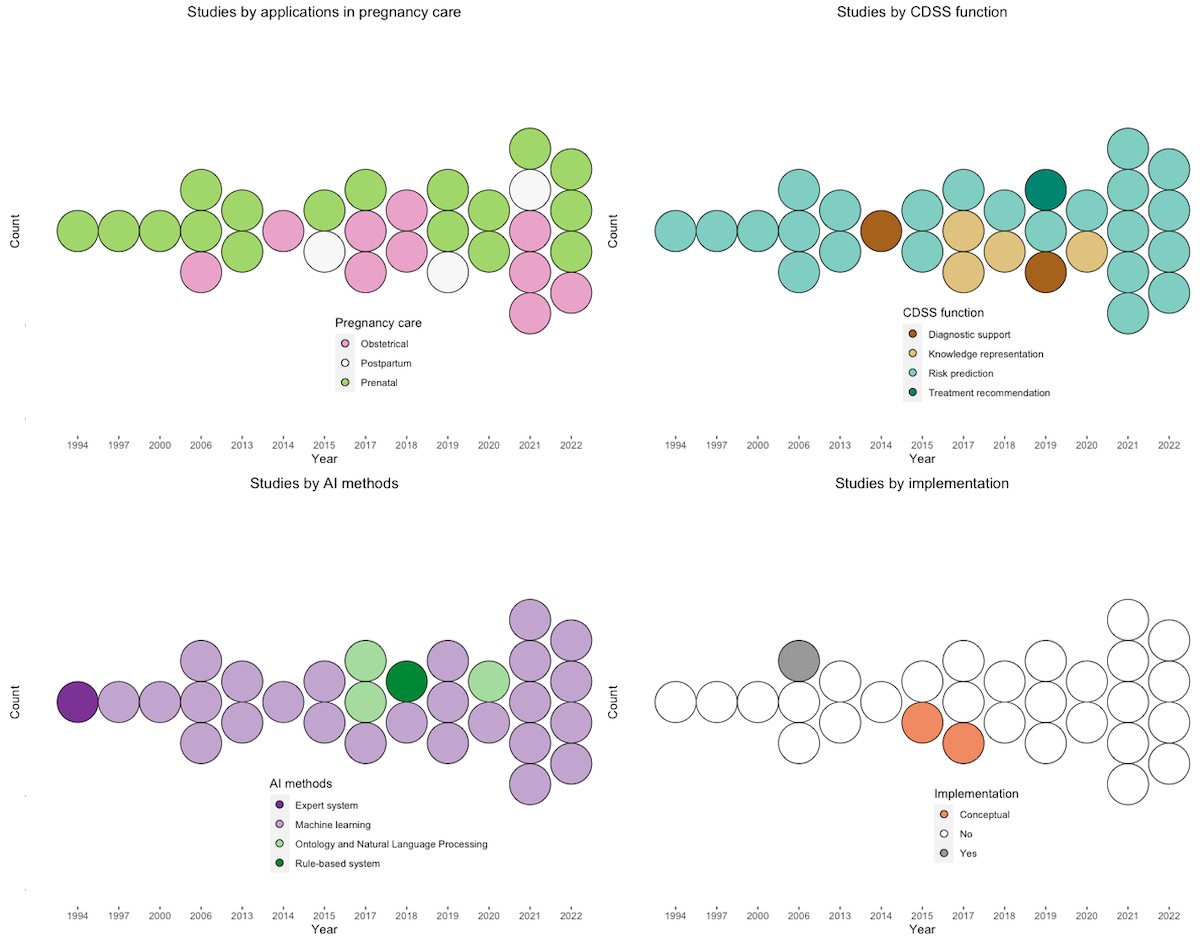

Our search identified 206 studies from PubMed/MEDLINE, 101 from Embase, and 377 from ACM Digital Library. After removing duplicates and studies based on exclusion criteria, 30 unique studies met the eligibility criteria (Figure 1). Analysis of these 30 studies revealed structured themes, summarized in Table 1, showing an overall increase in relevant studies over time, with a slight dip in 2013-2014 (Figure 2).

Table 1. Summary of reviewed studies on AI-augmented CDSS for pregnancy care.| Study | Study objectivesa | CDSSb functions | Data source | Sample | AIc methods | Performance | Validation | Implementation |

|—|—|—|—|—|—|—|—|—|

| Woolery and Grzymala-Busse (1994) [14] | Expert system for preterm birth risk assessment. | Risk prediction | Registry (multiple sites, United States) | 18,890 cases | Expert system, machine learning | ACCd 53%-88% | External | No |

| Mongelli et al (1997) [15] | Develop an expert system for the interpretation of fetal scalp acid-base status. | Risk prediction | Scalp blood samples (single, England) | 2174 samples | Logistic transformations, back-propagation networks, decision tree | N/Ae | Internal | No |

| Goodwin et al (2000) [16] | Predict preterm birth. | Risk prediction | EHRf (single, United States) | 19,970 patients | Rule induction, logistic regression, neural network | Customized (AUCg 0.75) | Internal | No |

| Catley et al (2006) [17] | Obstetrical outcome estimations in low-risk maternal populations. | Risk prediction | Registry (37 sites, Canada) | 48,000 cases | ANNh | ROCi 0.73 | Internal | No |

| Mueller et al (2006) [18] | Identify predictors to optimizeextubation decisions for premature infants. | Risk prediction | EHR (single, United States) | 183 infants | ANN, multiple layer regression | AUC >0.9 | Internal | Yes |

| Gorthi et al (2009) [19] | Predict pregnancy risk based on patterns from clinical parameters. | Risk prediction | Synthetic cases | 200 cases | Decision tree | ACC 82.5 | Internal | No |

| Ocak (2013) [20] | Assess fetal well-being. | Risk prediction | Cardiotocogram (single, United States) | 1831 samples | SVMj | ACC 99.3% | Internal | No |

| Yılmaz and Kılıkçıer (2013) [21] | Determine the fetal state using cardiotocogram data. | Risk prediction | Cardiotocogram (single, United States) | 2126 samples | LS-SVMk | ACC 91.62% | Internal | No |

| Spilka et al (2014) [22] | Examine cardiotocogram and support decision-making (outcomes: diagnostics and risk). | Diagnostic support | Cardiotocogram (single, United States) | 634 samples | Latent class analysis | N/A | Internal | No |

| Jiménez-Serrano et al (2015) [23] | Detect the postpartum depression during 1st week after childbirth. Toward a mobile health app. | Risk prediction | Registry (7 sites, Spain) | 1880 women | Logistic regression, naïve bayes, SVM, ANN | ANN (ACC 0.79) | Internal | Conceptual |

| Ravindran et al (2015) [24] | Assess fetal well-being. | Risk prediction | Cardiotocogram (single, United States) | 2126 samples | Ensemble: k-NNl, SVM, Bayesian network, and ELMm | ACC 93.61% | External | No |

| Paydar et al (2017) [25] | Predict pregnancy outcomes among systemic lupus erythematosus-affected pregnant women. | Risk prediction | EHR (single, Iran) | 149 pregnant women | MLPn, RBFo | MLP (ACC 0.91) | Internal | Conceptual |

| Dhombres et al (2017) [26] | Develop a knowledge base for ectopic pregnancy. | Knowledge representation | Ultrasound (single, England) | 4260 records | Ontology, NLP | Precision 0.83 | Internal | No |

| Maurice et al (2017) [27] | Develop a new knowledge base intelligent system for ultrasound imaging. | Knowledge representation | PubMed (single, United Kingdom) | N/A | Ontology, NLP | F 0.71 | Internal | No |

| Fergus et al (2018) [28] | Classify cesarean section and vaginal delivery. | Risk prediction | Registry (single, Czechia) | 552 pregnancies | Ensemble: RF, SVM, decision tree, ANN, deferred acceptance | Ensemble (AUC 0.96) | Internal | No |

| Seitinger et al (2018) [29] | Arden Syntax as medical knowledge representation and processing language in obstetrics. | Knowledge representation | N/A | N/A | Arden syntax | N/A | N/A | No |

| De Ramón Fernández et al (2019) [30] | Develop a decision support system to make suggestions for early treatment for ectopic pregnancy. | Treatment recommendation | EHR (single, Spain) | 406 tubal ectopic pregnancies | Multilayer perception, decision rule, SVM, Naïve Bayes | SVM (ACC 0.96) | Internal | No |

| Wang et al (2019) [31] | Develop a postpartum depression prediction model using EHR. | Risk prediction | EHR (single, United States) | 179,980 pregnancies | Logistic regression, SVM, decision tree, Naïve Bayes, XGBp, RFq | SVM (AUC 0.79) | Internal | No |

| Liu et al (2019) [32] | Predict pregnancies. | Diagnostic support | Mobile app | 65,276 women | Logistic regression, LSTMr | AUC 0.67 | External | No |

| Ye et al (2020) [33] | Predict GDMs and compare their performance with that of logistic regressions. | Risk prediction | EHR (single, China) | 22,242 singlet pregnancies | Gradient Boosting Decision Tree, AdaBoost, LightGBM, logistic regression, voting, XGB, decision tree, RF, logistic regressiont | GBDTu (AUC 0.74, 95% CI 0.71-0.76) | Internal | No |

| Silva et al (2020) [34] | Develop readable and minimal syntax for a web CDSS for antenatal care guidelines. | Knowledge representation | N/A | N/A | Ontology | N/A | No | No |

| Venkatesh et al (2021) [35] | Predict the risk of postpartum hemorrhage at labor admission. | Risk prediction | EHR (Consortium on Safe Labor, United States) | 228,438 deliveries | RF, XGB, logistic regressiont, lasso regressiont | XGB (C statistic0.93; 95% CI 0.92-0.93) | External (multi-site, multi-time) | No |

| Tissot and Pedebos (2021) [36] | Test embedding strategies in performing risk assessment of miscarriage before or during pregnancy. | Risk prediction | EHR (InfoSaude, Brazil) | 4676 pregnancies | Machine learning, ontology embedding | KRALv (F 0.76) | Internal | No |

| Escobar et al (2021) [37] | Predict risk of maternal, fetal, and neonatal events. | Risk prediction | EHR (15 sites, United States) | 303,678 deliveries | Gradient boosted, logistic regressiont | Gradient boosted (AUC 0.786) | External | No |

| Tao et al (2021) [38] | Construct a hybrid birth weight predicting classifier. | Risk prediction | EHR (single, China) | 5759 pregnant women | LSTM, CNNw, RF, SVM, BPNNx, logistic regression | Hybrid LSTM (MREy 5.65 ± 0.4) | Internal | No |

| Mooney et al (2021) [39] | Examine RF to predict the occurrence of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy | Risk prediction | Registry (2 sites, Sweden) | 53,000 deliveries | RF | RF (MCCz 0.63) | Internal | No |

| Du et al (2022) [40] | Predict gestational diabetes mellitus. | Risk prediction | Registry (single, Ireland) | 565 women | XBG, AdaBoost, SVM, RF, logistic regression | SVM (AUC 0.79) | Internal | No |

| Schmidt et al (2022) [41] | Predict adverse outcomes in patients with suspected preeclampsia | Risk prediction | Ultrasound (single, Germany) | 1647 patients | Gradient Boosting Decision Tree, RF | GBTree (AUC 0.81) | Internal | No |

| De Ramón Fernández et al (2022) [42] | Predict mode of delivery: cesarean section, eutocia vaginal delivery, instrumental vaginal delivery. | Risk prediction | Registry (single, Spain) | 10,565 records | MLP, RF, SVM | ACC >90 | Internal | No |

| Hershey et al (2022) [43] | Predict spontaneous preterm birth. | Risk prediction | Surveys, biospecimen (10 centers) | 2390 women | SVM | AUC 0.75 | Internal | No |

aThe outcomes of a CDSS model are given in italics.

bCDSS: clinical decision support system.

cAI: artificial intelligence.

dACC: accuracy.

eNot applicable.

fEHR: electronic health record.

gAUC: area under the receiver operating characteristic curve.

hANN: artificial neural network.

iROC: receiver operating characteristic curve.

jSVM: support vector machine.

kLS-SVM: least-squares support vector machine.

lk-NN: k-nearest neighbors.

mELM: extreme learning machine.

nMLP: multilayer perceptron neural network.

oRBF: radial basis functions neural network.

pXGB: XGBoost.

qRF: random forest.

rLSTM: long-short term memory.

sGDM: gestational diabetes.

tBenchmark algorithm

uGBDT: gradient-boosted decision tree.

vKRAL: knowledge representation and artificial learning.

wCNN: convolutional neural network.

xBPNN: back propagation neural network.

yMRE: mean relative error.

zMCC: Matthew’s correlation coefficient.

Figure 2. Trends in reviewed studies. Top-left: trends in studies by applications in pregnancy care. Top-right: trends in studies by CDSS function. Bottom-left: trends in studies by AI methods. Bottom-right: trends in studies by implementation. AI: artificial intelligence; CDSS: clinical decision support system.

Risk of Bias of Included Studies

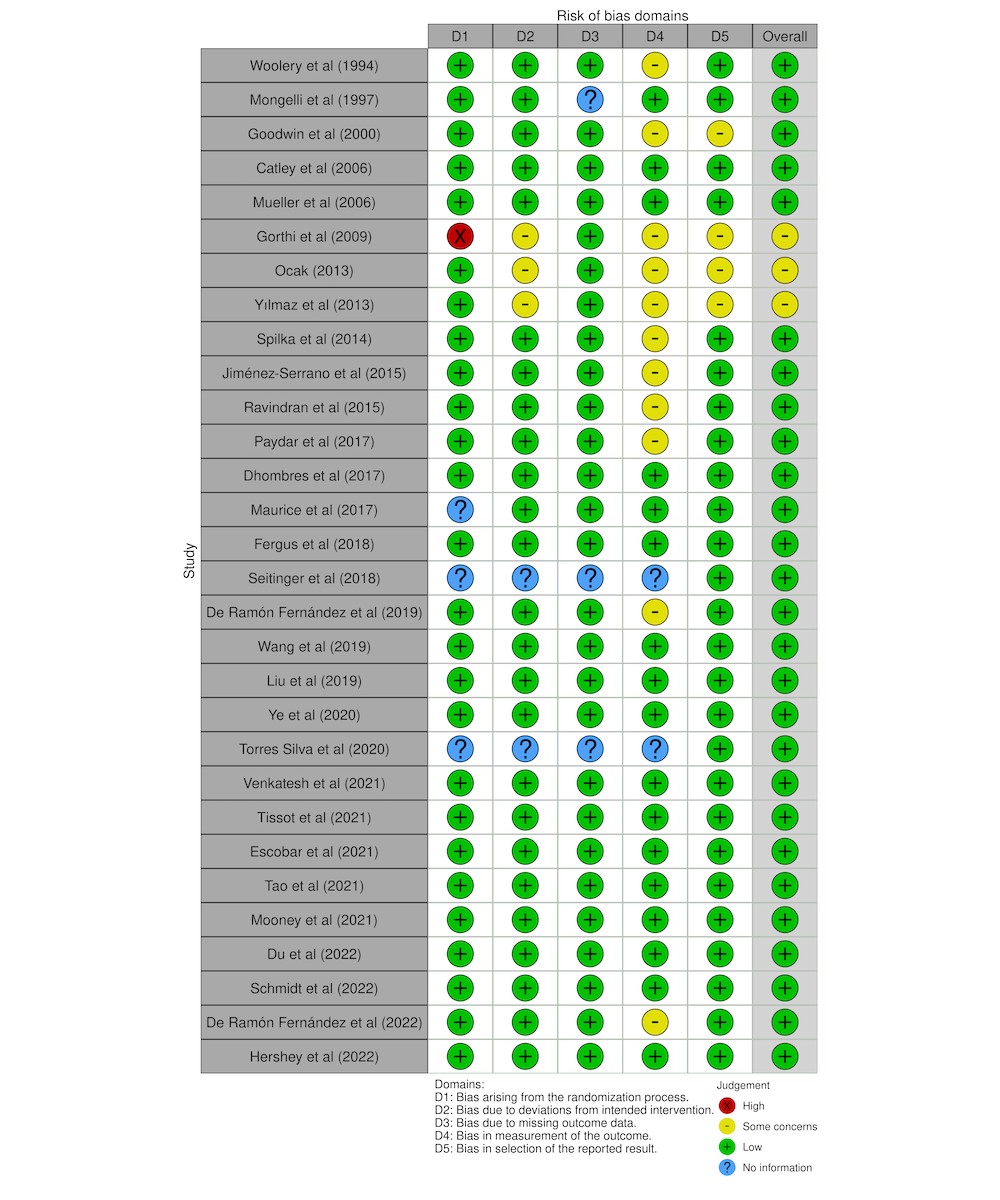

Among the 109 screened studies, 22 were excluded for not being empirically based, 37 for not primarily focusing on pregnancy care, and 22 for not developing or applying AI methods despite using AI-related terms. This rigorous appraisal yielded 30 studies with full quality agreement between reviewers TL and NG, confirmed by reviewer CL. Figure 1 details the numbers of included and excluded studies at each stage. Following PRISMA guidelines, the risk of bias assessment is summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Traffic light plot for risk-of-bias assessment of included studies.

Study Characteristics: Applications in Pregnancy Care

Prenatal and Early Pregnancy Care

The most critical application area is the detection of maternal and fetal risk factors and abnormalities during prenatal care, vital for timely intervention (n=17, 57%). CDSS tools are used to predict conditions such as gestational diabetes mellitus [33,40], miscarriage [25,36], and adverse outcomes from preeclampsia [41] using data from medical history and prenatal visits. Another significant application is in ectopic pregnancy, a life-threatening condition [30]. AI-driven CDSS aids in making informed decisions about treatment following an ectopic pregnancy diagnosis [30].

Obstetrical Care

Given the concerning rates of maternal morbidity and mortality in the US and globally [44], a growing number of CDSS studies focus on predictive models for early detection of adverse events during obstetrical care (n=10, 33%). Identifying individuals at risk for preterm birth, for example, allows for advanced care planning [14,17,43]. These studies often analyze risk factors contributing to adverse events, using machine learning to identify data indicative of negative outcomes. Computer-assisted cardiotocography (CTG) interpretation, used before or during labor, is another key application to support decision-making [21,22,28].

Postpartum Care

CDSS is also applied to estimate the risk of postpartum hemorrhage upon labor and delivery admission (n=3, 30%). Postpartum hemorrhage is a leading cause of maternal mortality and morbidity [45]. While traditional risk assessments rely on medical record stratification using statistical models, recent CDSS research explores factors beyond known risks [35], aiming to better understand individual variations and reduce biases from standard guidelines. Risk assessment and screening for postpartum depression, a common but underdiagnosed condition, is another important area of CDSS application [23,31].

Study Characteristics: Functionality of CDSSs

Diagnostic Support

Diagnostic support, a foundational CDSS function (n=2, 7%) [46], is used in pregnancy care to aid CTG interpretation [21,22,28]. CTG interpretation is challenging due to inter-observer variability, yet accurate interpretation is vital for clinical decisions during prenatal care and labor (e.g., cesarean vs. vaginal delivery). Diagnostic support also extends to pregnancy identification using mobile device data [32], potentially valuable for family planning and preventative care.

Clinical Risk Prediction

Clinical risk prediction has become a prominent CDSS function in pregnancy care (n=22, 73%). These tools are broadly used for the early detection of adverse maternal and fetal events, particularly those benefiting from early intervention. Applications include predicting eclampsia or preeclampsia [37,41], gestational diabetes [33,40], preterm birth [14,17], miscarriage [25,36], perinatal hemorrhage [35,37,41], hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy [39], low birth weight [38], and postpartum depression [23,31]. EHRs and medical images are frequently used to train these predictive models, with some studies utilizing mobile app data [23,32].

Therapeutics Recommendation

Guiding decisions on the mode of delivery is a critical aspect of obstetric care (n=2, 7%). With rising rates of cesarean deliveries and associated risks [47], CDSS studies explore the feasibility of using machine learning to recommend delivery modes: cesarean section, eutocic vaginal delivery, and instrumental vaginal delivery [42].

Knowledge Base

CDSS can be knowledge-based or independent of a knowledge base (n=4, 13%). Several studies focus on designing and building knowledge bases to support pregnancy care CDSS. These knowledge bases use formats like Arden syntax and ontology for representing clinical guidelines and medical knowledge, and XML for web and mobile CDSS applications. Ontology, in particular, supports diagnostics and treatment recommendations for ectopic pregnancy and annotating medical images like obstetric ultrasounds [26,27]. Arden syntax formalizes obstetric guidelines for CDSS functions [29], while XML encodes knowledge bases for mobile prenatal care CDSS [34].

Study Characteristics: AI Methodologies and Applications

Algorithms

Knowledge-independent CDSS typically use computational algorithms for decision boundary learning. Supervised algorithms (classification, prediction) require labeled data, while unsupervised algorithms (clustering) operate without. Regression algorithms are commonly used benchmarks for prediction, diagnostic support, and treatment recommendations. Parametric linear statistical models also serve as benchmarks [35]. Among supervised machine learning algorithms, support vector machines, random forests, and gradient boosting (e.g., XGBoost) are increasingly used for their high performance. Simpler neural networks (multilayer perceptron, artificial neural networks) are also employed, especially when feature spaces are less complex [17,18,30]. Ontology embedding is used to integrate medical knowledge into machine learning models in pregnancy care [36]. Deep learning algorithms (convolutional and recurrent neural networks) are also emerging, showing superior performance in some applications [38].

Knowledge-based CDSS relies on rules (if-then, fuzzy logic) or semantic relations (ontology-defined properties). Natural language processing (NLP) is used with ontology-based knowledge bases for medical image annotation [26,27]. Rule-based algorithms demonstrate feasibility and clinical interpretability [16]. Ontology is a common choice for constructing knowledge bases (n=2, 7%) [26,27].

Performance Evaluation

Most studies (n=28, 93%) validate models internally using hold-out, n-fold cross-validation, or bootstrap methods. Evaluation metrics include precision, recall, F-measure, AUC [48], mean squared prediction error, Matthew’s correlation coefficient, chi-square, c-index, accuracy, and customized accuracy measures. Some studies report confidence intervals [33,35], enhancing result interpretability. External validation is less common (5 studies, 16%) [14,24,32,35,37], testing CDSS on separate datasets, including those from different clinical sites.

Treatment With Possible Bias

Biases in data sampling, processing, model training, validation, and algorithm design can skew CDSS performance and clinical decisions. Untrained data and poorly sampled data can bias AI-augmented systems like CDSS, yet existing studies often lack comprehensive discussion on bias remediation. Even imputation methods can amplify biases if sample biases are not recognized. Our review found no comprehensive treatment or discussion of mitigating potential biases in CDSS design and development.

Study Characteristics: CDSS Implementation

CDSS implementation, crucial for translating research into practice, is rarely discussed beyond conceptual or pilot study designs (n=3, 10%) [18,23,25]. Implementation studies use web-based data entry and graphical result presentation [18,25], with one study demonstrating an Android-based interface [23]. Comprehensive implementation study designs, including usability testing, are absent from the reviewed studies.

Discussion

Principal Findings

The proliferation of AI in clinical medicine over recent decades has not been matched by systematic reviews of AI-augmented CDSS in obstetrics and gynecology. This review addresses this gap, assessing studies by application, functionality, methodology, and implementation to provide a state-of-the-art overview, highlighting advantages, limitations, and future directions. We identified 30 relevant studies (1994-2022), showing an increasing trend, particularly post-2021. Studies primarily used EHR, registry, and mobile device data, except for knowledge base development studies. CDSS functions in pregnancy care include diagnostic support, clinical prediction, therapeutics recommendation, and knowledge bases. Traditional CDSS functions like patient safety alerts, clinical management prompts, and administrative support are less represented in pregnancy care CDSS [49–51]. CDSS architectures are both knowledge-based (ontology, NLP) and knowledge-independent (machine learning). Machine learning, ontology, and NLP are increasingly central to modern pregnancy care CDSS.

Clinical Implication

Adopting AI-augmented CDSS in pregnancy care presents both potentials and challenges. Firstly, model performance in individual pregnancy episodes is promising. CDSS tools are designed for prenatal, obstetrical, and postpartum care, predominantly focusing on prenatal risk prediction for miscarriage [36], ectopic pregnancy [26,30], gestational diabetes [33,40], preterm birth [14,16,17], and severe maternal morbidity [41]. While predictive performance is generally good, the practical lead time for reliable risk detection before adverse events needs clarification before real-world application. Obstetrical CDSS applications show potential in delivery mode selection [28,42], preterm infant extubation [18], and intrapartum diagnostics [22]. Postpartum CDSS effectively supports postpartum hemorrhage [52] and depression risk detection [23,31], though real-world data collection post-partum via mobile apps can be challenging.

Secondly, model interoperability is crucial for clinical interpretability and clinician acceptance. Knowledge-based CDSS, particularly those using ontologies [26,27,34,36], offer high interpretability due to traceable knowledge and semantic reasoning. Predictive CDSS models include parametric models (regression, decision trees, shallow neural networks, expert systems) [14–19,23,25,28,30–33,37,38,40,42,52], which are more transparent in decision logic, and non-parametric/deep learning models [20,21,28,30,38,42,43], which excel with large, complex datasets but are less interpretable.

Data availability and quality pose significant hurdles. Pregnancy care data is often fragmented across hospitals, outpatient groups, and labs, with varying data entry protocols. Inconsistent prenatal care initiation and frequency further complicate data collection, as poorer outcomes correlate with late and infrequent care [53]. This data inequality is often underestimated in CDSS design and testing, potentially biasing real-world application.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions of Reviewed Studies

Overview

This review reveals strengths in pregnancy care CDSS design but also highlights limitations and future directions due to the field’s early stage.

Toward Robustness in Internal Validation Design

Strengths include: (1) Use of real-world EHR, registry, and mobile device data, with some multi-center studies [14,17,23,37,39,43]. While most studies have adequate sample sizes, some use smaller samples (n=100-300, Table 1). (2) Comparison of multiple AI algorithms against benchmarks in most studies (n=19, 73%). (3) Common use of cross-validation or hold-out methods for internal validation. (4) Use of F-score, AUC, and probabilistic statistics for performance metrics; though some studies rely solely on accuracy, which is less comprehensive. Overall, reported model performance is acceptable (Table 1).

Clinical Plausibility

(1) Most studies explicitly state clinical use cases, emphasizing early detection of abnormalities and at-risk pregnancies as core clinical benefits. However, prenatal data scarcity and integration challenges limit early diagnosis and prediction. (2) Studies address diagnostics and therapeutics specific to pregnancy care, like CTG interpretation and delivery mode selection. However, CTG interpretation’s inter-rater variability necessitates repeated CDSS evaluations. Delivery mode selection CDSS has not yet considered fetal or subsequent maternal outcomes [47], limiting clinical utility. Emergency care applications for AI-augmented CDSS are also underexplored.

Possible Biases

CDSS can introduce biases through (1) data sampling for training and testing, and (2) racial and ethnic disparities in maternal health [54]. Training CDSS on data from specific socioeconomic groups can bias predictions. CDSS design and implementation for pregnancy care should consider targeted populations and social determinants of health (SDOH). The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends SDOH screenings to mitigate bias [55]. However, current studies lack strategies to reduce biases, a critical future direction.

External Validation and Implementation

External validation and implementation are rare, despite conceptual discussions. Without external validation, CDSS usability across different patient groups, healthcare systems, and timeframes remains unproven. Challenges include CDSS model interoperability with clinical systems and implementation requirements like organizational commitment, workflow integration, usability testing, and staff training [56]. Generalizability of machine learning models is a key challenge. Future research should address these gaps.

Limitations of This Study

This review has limitations. The keyword and MeSH term-based search strategy may not capture all relevant CDSS studies, especially those not explicitly using CDSS terminology. The loosely defined nature of CDSS is also a limitation. Despite these limitations, this review provides timely and relevant insights to guide evidence-based practice and future CDSS research in pregnancy care. This study adhered to PRISMA guidelines and used dual independent reviewers for study selection and evaluation.

Conclusions

This review summarizes the state of AI-augmented CDSS in pregnancy care, highlighting machine learning-based predictive models and computer-aided diagnostics with good internal validity. Advances include CDSS for early prenatal abnormality diagnosis, at-risk pregnancy detection, and knowledge bases for image annotation and clinical guidelines. Future directions should focus on addressing AI and CDSS biases, enhancing external validity and clinical implementation, and improving CDSS clinical plausibility.

Acknowledgments

This research received no specific funding.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

Multimedia Appendix 1PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) checklist.

PDF File (Adobe PDF File), 623 KB

Multimedia Appendix 2Search strings.

References

[References]

Abbreviations

| AI: artificial intelligence |

|---|

| CDSS: clinical decision support systems |

| CTG: cardiotocography |

| EHR: electronic health record |

| MeSH: Medical Subject Headings |

| NLP: natural language processing |

| PMC: PubMed Central |

| PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| SDOH: social determinants of health |

Edited by A Mavragani; submitted 20.11.23; peer-reviewed by S Kommireddy, N Fareed, G Carot-Sans, M Galani; comments to author 06.04.24; revised version received 06.05.24; accepted 24.07.24; published 16.09.24.

Copyright ©Xinnian Lin, Chen Liang, Jihong Liu, Tianchu Lyu, Nadia Ghumman, Berry Campbell. Originally published in the Journal of Medical Internet Research (https://www.jmir.org), 16.09.2024.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work, first published in the Journal of Medical Internet Research (ISSN 1438-8871), is properly cited. The complete bibliographic information, a link to the original publication on https://www.jmir.org/, as well as this copyright and license information must be included.